Ginkgos of The British Isles: cartographic collage, crowdsourcing and obsession on Instagram

Claire Reddleman

“I hope you will consider what I have arranged. And be sceptical of it.”

John Berger, Ways of Seeing, Episode One (BBC, 1972)

An atlas of obsessive attention

In 2019, I became obsessed with ginkgo biloba trees. I hadn’t intended to…

#GinkgosOfTheBritishIsles is a visual research project looking at the popular tree species Ginkgo biloba. The project crowd-sourced photos of ginkos in Britain from Instagram users, in order to bring them together with maps, to create a sort of co-produced view of how this particular introduced species is experienced as part of the visual life of the British Isles.

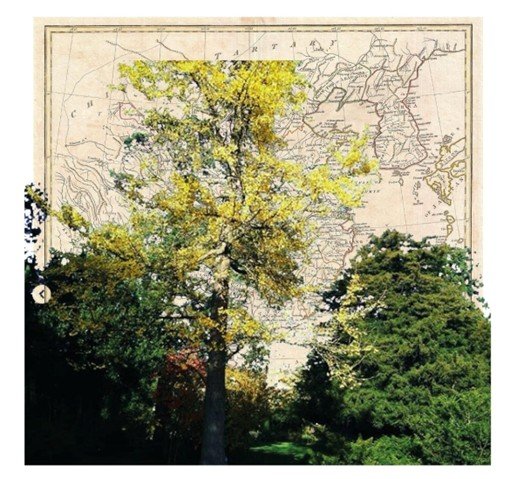

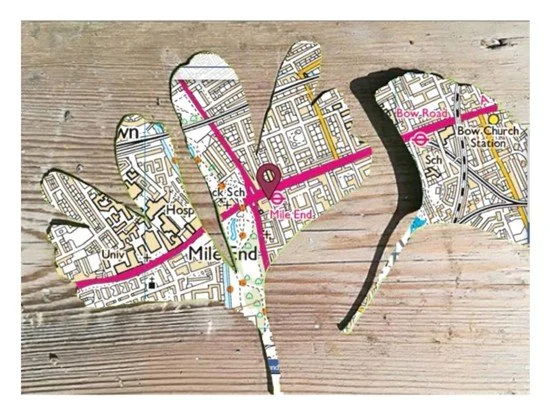

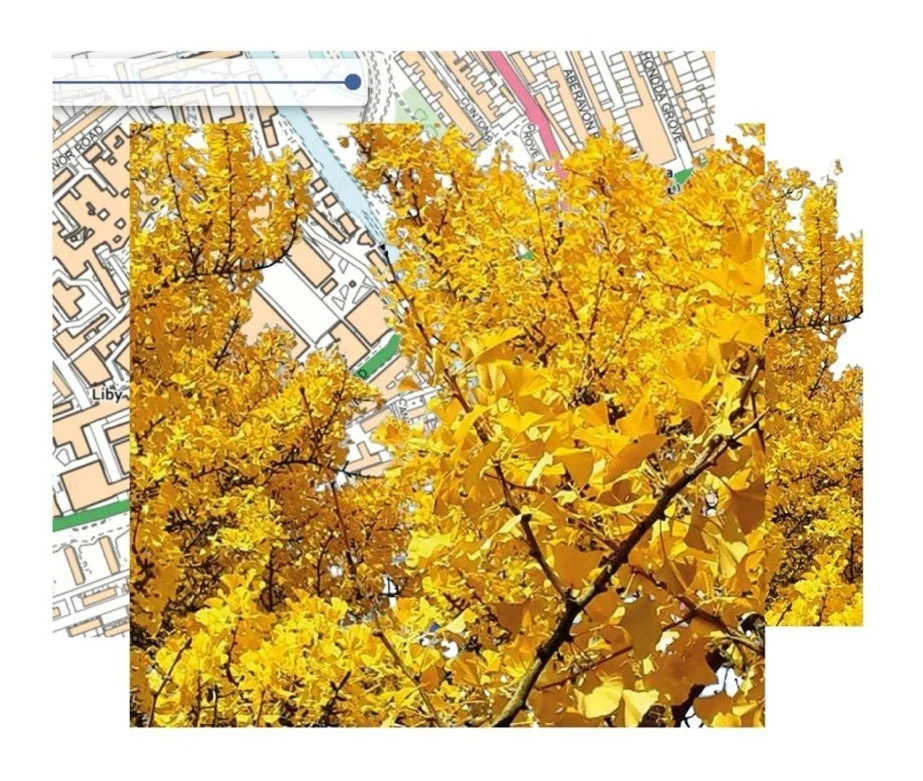

Contributed photos were paired with map images of the species’ places of origin: Japan, where the tree was encountered by the German surgeon and traveller Engelbert Kaempfer in 1692; China, where the species is native; Leiden, where ginkgo arrived in Europe from Japan; and Mile End, London, where the first seedling in Britain was raised in 1750. Documentary photography was also carried out at the National Plant Collection of Ginkgo biloba and cultivars, held by Tony Davies in Worcestershire. I now think of these photographs and collages as forming an idiosyncratic atlas, intertwining ‘the ginkgo’ as the subject with our ways of fetishizing and loving it.

I alighted on ginkgo as the focus for the project while I was thinking about a larger research project about the ways in which the nation or nations that exist in ‘these islands’ is made up, or collaged, of materials from around the world. Not ‘new’ materialism, but old.

I had previously been working at the Royal Horticultural Society and became interested in the history of the plant hunters and plant introductions to this tiny archipelago. I was also teaching about digital media, working with students who wanted to carry out endless projects about social media platforms. I thought about the possibility of considering trees as a political realm in which debates about belonging, being native, and invasiveness are played out. How long does a tree species have to have lived here before it is considered to be from here, to belong?

I looked at the way that social media platforms, especially the photo-driven Instagram, channel our attention, often into fetishisation. Ginkgo is loved, revered, and celebrated on Instagram. I wondered if I could ask Insta users to contribute their photographs of ginkgos from around these islands, photographs I could collect as I collect fallen ginkgo leaves. A small but enthusiastic group of users got involved. I collaged their contributions with maps in hope of offering a multiplied, expansive view of ginkgos in the British Isles – against the fetishising of social media, but with curiosity about what we pay attention to and value.

I invited cultural geographer Jan Van Duppen to contribute a response to the project, and he put together a thoughtful commentary of reflections and quotations called ‘Transplantation: A response in fragments’, which is reproduced below. He invites the reader ‘to loiter amongst these fragments’, and the collection of fragments and their assembling into a new whole reflected, to my mind, the habits of collecting leaves from the ground and pressing them between notebook pages, as well as the logic of collage itself.

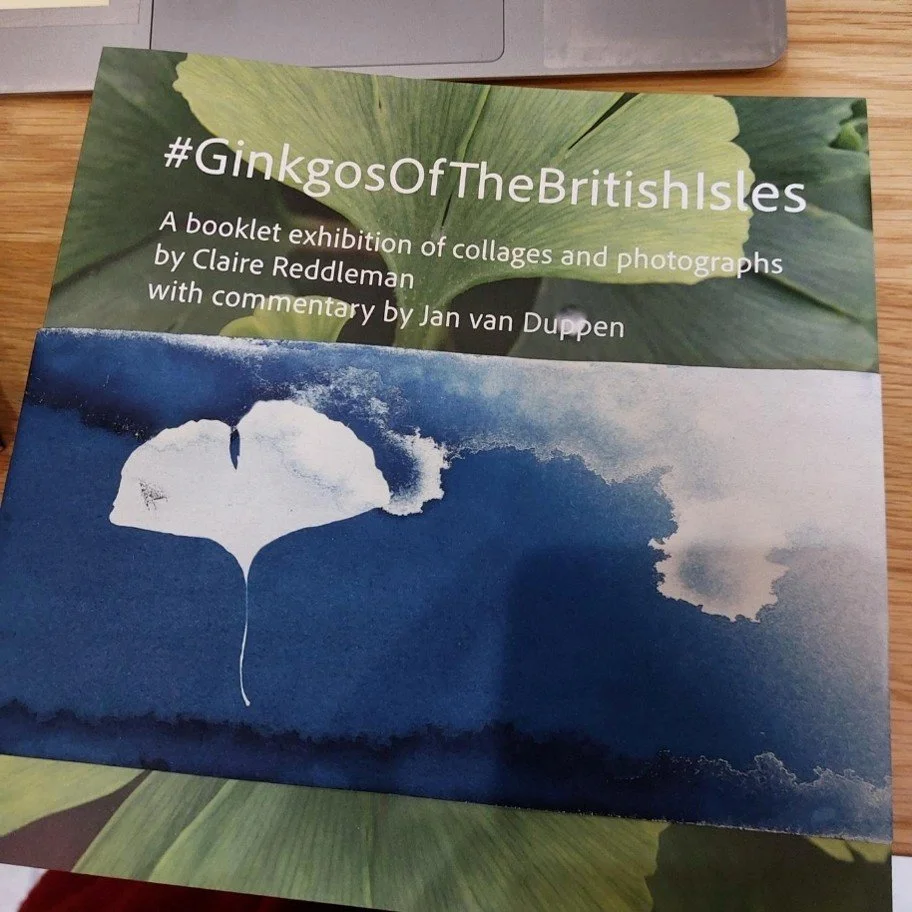

The series of twelve collages, and a selection of photographs of the National Collection, were later showcased in booklet form, when I was invited to exhibit a project as part of the Livingmaps Network Conference 2025, with the theme of ‘more-than-human mappings’.

The project was originally funded by the Kings College London Innovation Fund, and the booklet was funded by the University of Manchester School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Staff Development Fund.

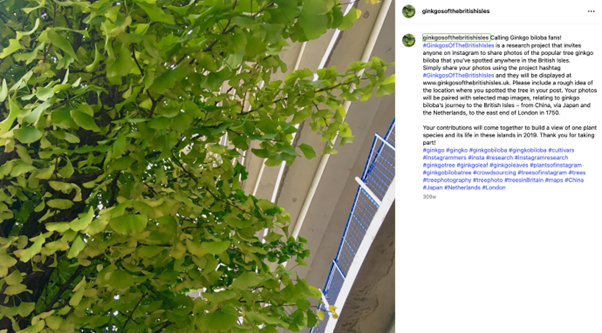

Figure 1. Screengrab showing the most recent posts on the Instagram account

Crowdsourcing images on Instagram

The project has an Instagram account, #ginkgosofthebritishisles, which began by extending an invitation to users to share their photos:

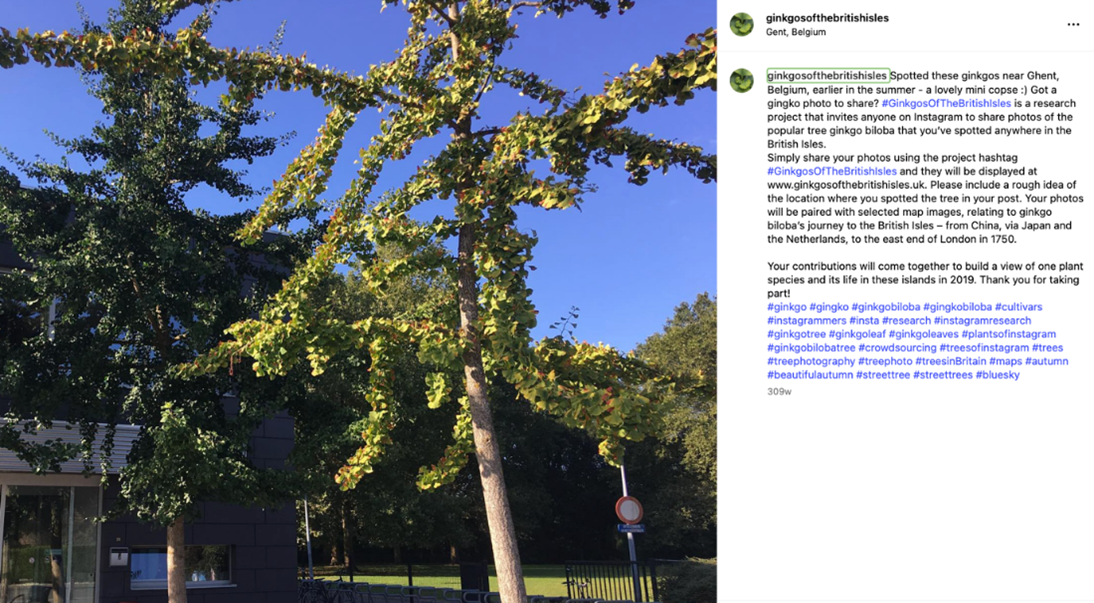

#Ginkgos of the British Isles is an academic research project that invites anyone on Instagram to share photos of specimens of the popular tree ginkgo biloba that you’ve spotted anywhere in the British Isles. Simply share your photos using the project hashtag #ginkgosofthebritishisles and they will be included on this site. Your photos will then be paired with selected map images, relating to ginkgo bilobas journey to the British Isles – from China, via Japan and the Netherlands, to the east end of London in 1750. Your contributions will come together to build a view of one plant species and its life in contemporary Britain.

Figure 2. The first Instagram post of #ginkgosofthebritishisles

I wrote out all the hashtags in a note on my phone, so I could use them consistently (varying the place names):

#ginkgo #gingko #ginkgobiloba #gingkobiloba #cultivars #instagrammers #insta #research #instagramresearch #ginkgotree #ginkgoleaf #ginkgoleaves #plantsofinstagram #ginkgobilobatree #crowdsourcing #treesofinstagram #trees #treephotography #treephoto #treesinBritain #maps #China #Japan #Netherlands #London #stpaulscathedral #autumn #autumnvibes🍁 #autumnbeauty

The account soon turned into a space for me to share photos of ginkgos I was spotting, and sharing from my photo collection of past sightings, as I reiterated the call for users to share their own images. Surely, I thought, at this point I was joining in with the fetishization I had sought to critique.

Figure 3. Posting a photo of a ginkgo I took near Ghent, Belgium

About the research: background

‘We never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves. Our vision is continually active, continually moving, continuously holding things in a circle around itself, constituting what is present to us as we are’. (John Berger) [1]

This project represented a new departure for me in terms of methods, extending research interests in collage and plant collecting I had been developing through postdoctoral research, as well as independent creative work. In previous research, particularly my book Cartographic Abstraction in Contemporary Art: Seeing with Maps[2] and an article Disrupting the cartographic view from nowhere: ‘hating empire properly’ in Layla Curtis’s cartographic collage ‘The Thames.[3] I have theorised how artworks that engage with maps and mapping techniques can shed light on how maps position us as viewers and foster relationships with the world that enable us to gain knowledge as well as to mediate power relations. I have written about maps as demonstrating certain aspects of artistic collage techniques, and the trope of collage as a method for combining disparate elements into a new whole is one that I intend to keep exploring in new ways.

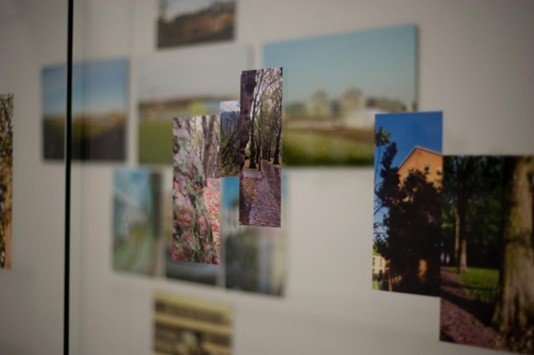

This research links with my broader interest in visual culture, and my artistic practice as a photographer. I have previously exhibited collaborative, collage-based photographic work looking at the idea of trees in everyday life and how we perceive them, in an exhibition held at Goldsmiths, University of London, with the late John Levett in, I think, 2016:

Figure 4. Installation view of 'Archive of the Yet to Become', with my photo-strips taped to the glass and John’s photographs in the cabinet behind.

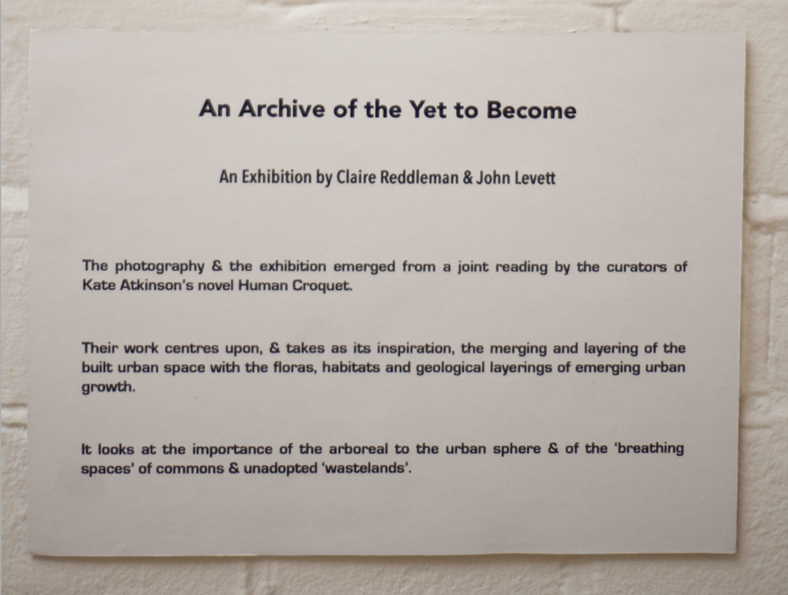

My first step in the collaging was cutting photographs into strips and simply placing them next to and over one another. I thought of my part of the project as being called ‘Streets of Trees’, a reference to Kate Atkinson’s novel Human Croquet.[4] It got a mention in our exhibition blurb, but otherwise the idea was rather lost in the presentation.

Figure 5. The exhibition blurb

Later, I was given the opportunity to expand and extend my ways of making collage. I carried out postdoctoral work on ‘Postcards from the Bagne’, led by Dr Sophie Fuggle and funded by the AHRC, exploring how French penal colonies have been mapped and photographed, historically as well as in the contemporary context of penal heritage and associated tourism. I wrote in a little more detail about this project in Living Map Review 11. As part of this project, I created a digital photographic archive of former penal sites[5] as well as collecting plant samples and soil samples for use in original artistic collages involving photography and cartography of the penal colonies. I thought about the ways we can relate to plants as markers of place, as being made to ‘stand for’, in a metaphorical register, the places where they live.

Figure 6: 'Untitled (After Jim Lambie)' (left), and ‘Untitled (Fort Teremba, Nouvelle Calédonie)’ (right), two of the collages made as part of Postcards from the Bagne

This engagement with plants and the politics of whether plants are classified as native or non-native, encouraged me, at that time, to develop a much larger research idea, ‘Planting the Nation’. The intention was to explore how the history of plant introduction in Britain could be engaged with using visual methods, in order to contribute to a future imaginary of Britain as a global place that is materially constituted (in part) through plant introduction. Many introduced plants have become garden favourites, and I was interested in whether people’s feelings and opinions about multiculturalism can be affected by greater understanding of those plants’ histories. It was too large a project to embark on at that stage, so I thought it would be useful to develop projects that might contribute to my having a better understanding of what research methods would best serve my research interests and best facilitate participation using visual methods.

I had previously used social media (Twitter and Instagram) as dissemination tools but had not yet tried to use them as a participatory research method. I was keen to experiment with using Instagram as a participatory research tool because it prioritises photography and has developed large audiences interested in plants, horticulture, and amateur and professional plant photography.

Research questions

Can visual approaches to the history of plant introductions to the British Isles help to develop an imaginary of Britain as an island place that is constituted from global sources?

Can focusing in on one species offer a useful way of engaging this complex history, which is vast and includes multiple academic disciplines such as botany, environmental sciences, history, travel narratives, botanical history, etc.?

Can Instagram function as a helpful research device, enabling potentially hundreds of people to participate by contributing photographs to the project Instagram hashtag?

Can photography and cartographic images be brought together in an online presentation, in order both to stimulate interest in the geographical relationships embodied in the chosen plant species, and to explore further the ways of viewing the world that photography and cartography make possible?

A note about naming

I went round and round about what the project could be named. Every configuration seemed to have drawbacks. In the end, I shared this statement on the project webpage:

At this moment in the cultural and political life of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, it is not entirely straightforward to refer to this group of islands by name. I have opted for ‘British Isles’ because I think it will be more widely recognised than other alternatives, such as ‘British Archipelago’ (meaning group of islands), while still emphasising the character of this place as a collection of islands.

I have chosen not to use ‘Great Britain’ because that name doesn’t include Northern Ireland; and because Northern Ireland is part of the UK, I am curious about the presence of ginkgo biloba there and in the whole island of Ireland. The political entity into which ginkgo biloba was introduced in London in 1750 was known as the ‘Kingdom of Great Britain’, incorporating the then ‘Kingdom of Scotland’ and the ‘Kingdom of England’ which included Wales. Since 1750, ginkgo biloba has been widely planted as a street tree and has a presence at least as far south as London, as far north as North Queensferry, and is widely available in garden centres in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland (which I take to mean it is being planted in private gardens). I hope this project will offer a way to gather a picture of ginkgo biloba across the whole of these islands in 2019.

The collages

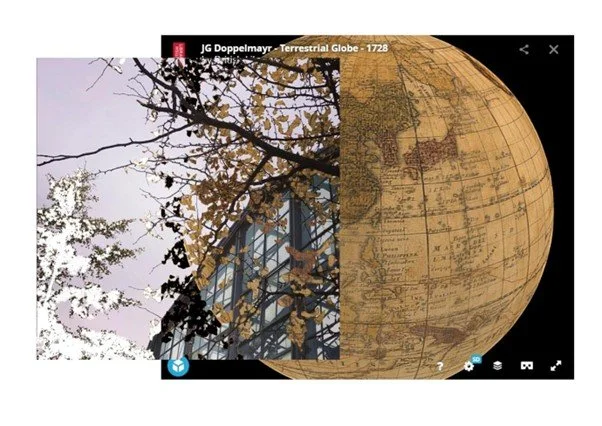

Figure 7. Photograph submitted by nylon and celluloid, taken at Kew Gardens

Map: Globus Terrestrius by Johann Gabriel Doppelmayr. Nuremberg, 1728. 1 globe, 31 cm. in diameter, mounted on a four-legged wooden stand with a meridian ring and hour ring. 3D model available at: https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/jg-doppelmayr-terrestrial-globe-1728-4337d6b3728e4c529f4ba562e20db35a

British Library record available at: http://explore.bl.uk/primo_library/libweb/action/dlDisplay.do?vid=BLVU1&search_scope=LSCOP-ALL&docId=BLL01013006161&fn=permalink

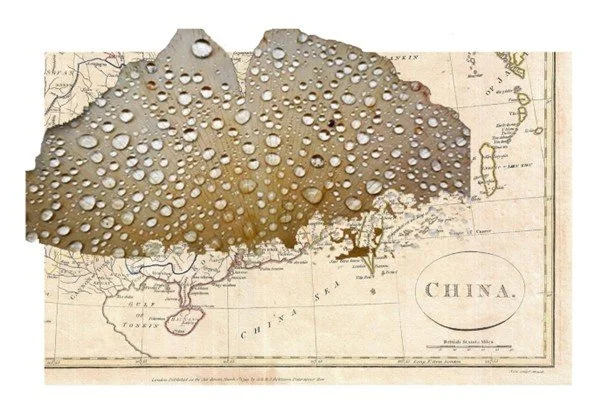

Figure 8. Photograph submitted by lelly young, taken in their garden, from seed collected in Greenwich Park, London. Map: 1799 Clement Cruttwell Map of China, Korea, and Taiwan. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1799_Clement_Cruttwell_Map_of_China,_Korea,_and_Taiwan_-_Geographicus_-_China-cruttwell-1799.jpg

Figure 9. Photograph submitted by sheree_9, taken at Myddelton House Gardens, Lee Valley, London. Map: 1799 Clement Cruttwell Map of China, Korea, and Taiwan. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1799_Clement_Cruttwell_Map_of_China,_Korea,_and_Taiwan_-_Geographicus_-_China-cruttwell-1799.jpg

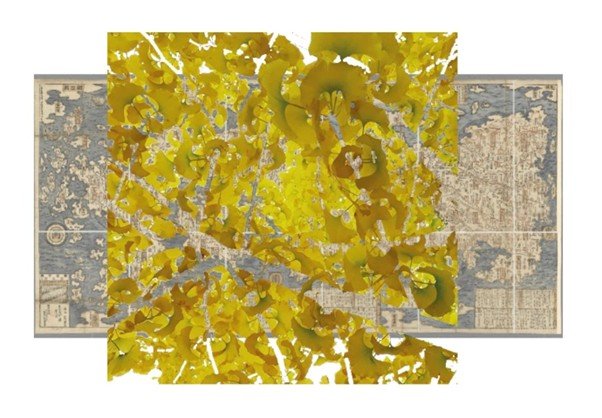

Figure 10. Photograph submitted by lelly_young, location unknown. Map: Dainihonkoku oezu [Large map of Great Japan], Creator Ishikawa Tomonobu (ca. 1661-ca. 1721). Part of the British Library collection. Available at: https://mapwarper.h-gis.jp/maps/3959#

Figure 11. Photograph submitted by sheree_9, taken at Myddelton House Gardens, Lee Valley, London. Map: Oorspr. verschenen in: François Halma’s Tooneel der Vereenighde Nederlanden [...]. - Te Leeuwarden : by Henrik Halma [...], 1725 (rechtsboven binnen het kader: ‘II deel. Fol: 272.’), Utrecht University, Netherlands. Available at: https://objects.library.uu.nl/reader/1874-20551?lan=en&page=1 uu.nl/reader/index.php?obj=1874-

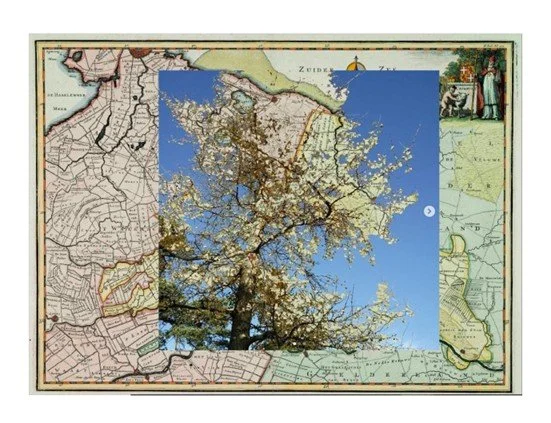

Figure 12. Photograph submitted by dendrologista, location unknown. Map: Oorspr. verschenen in: François Halma’s Tooneel der Vereenighde Nederlanden [...]. - Te Leeuwarden : by Henrik Halma [...], 1725 (rechtsboven binnen het kader: ‘II deel. Fol: 272.’), Utrecht University, Netherlands. Available at: http://objects.library.uu.nl/reader/index.php?obj=1874-20551&lan=en#page//34/13/50/34135078771523366245615626729484563466.jpg/mode/1u

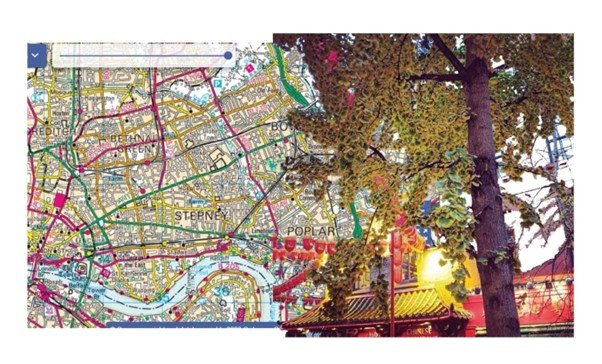

Figure 13. Photograph submitted by trees-london, taken at Farringdon, London. Map: Ordnance Survey data (c) Crown copyright and database rights 2020.

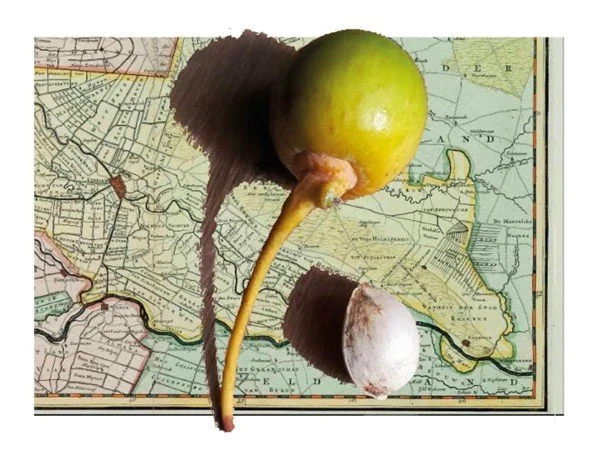

Figure 14. Photograph submitted by sheree_9, taken at Myddelton House Gardens, Lee Valley, London. Map: Ordnance Survey data (c) Crown copyright and database rights 2020.

Figure 15. Photograph submitted by trees-london, taken in Chinatown, London. Map: Ordnance Survey data (c) Crown copyright and database rights 2020.

Figure 16. Photograph submitted by dendrologista, taken near Bath. Map: An accurate MAP of the Country TWENTY MILES round LONDON. From GRAVESEND to WINDSOR East and West, and from ST. ALBANS to WESTERHAM North and South with the CIRCUIT of the PENNY POST / J. Cary sculp. John Fielding, (Bookseller), publisher. London: Published by I. Fielding No. 23, Pater-noster Row, July 1, 1782. British Library.

Figure 17. Photograph submitted by dendrologista, location unknown. Map: Ordnance Survey data (c) Crown copyright and database rights 2020.

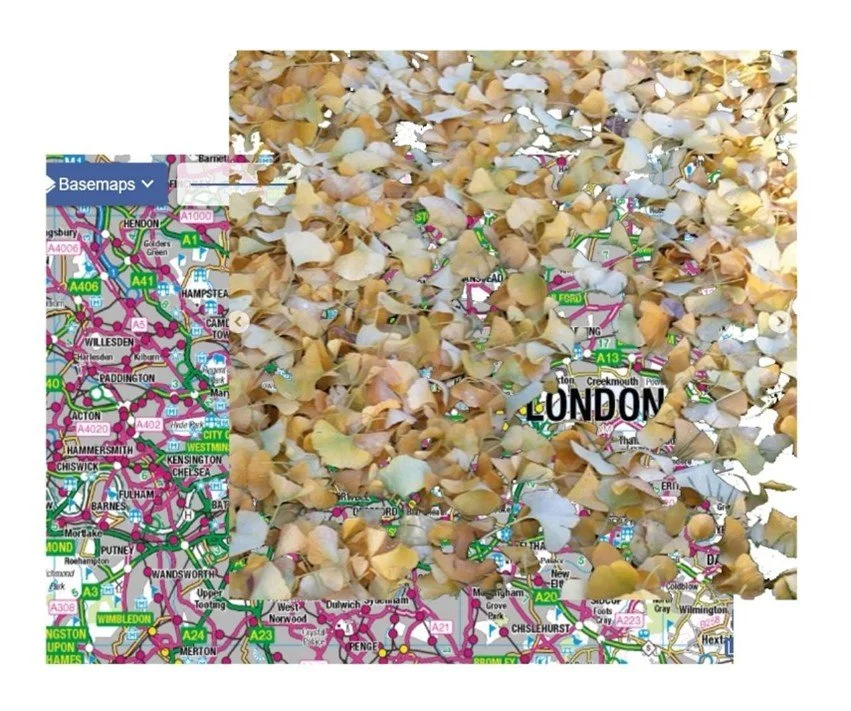

Figure 18. Photograph submitted by lelly young, taken at Dulwich, London. Map: Ordnance Survey data (c) Crown copyright and database rights 2020.

The National Collection of ginkgo biloba and cultivars - www.npcginkgo.org

In the garden of an ordinary house in Worcestershire lives the National Collection of ginkgo biloba and cultivars. It is cared for by expert horticulturist Tony Davies; the collection may be visited by appointment.

“Put simply, a National Plant Collection is a registered and documented collection of a group of plants. These can be linked botanically by plant group or perhaps have a shared history or geography (in which case they may not all be the same type of plant). Today there are over 720 National Collections, safeguarding nearly 100,000 different plants. Together, this living library represents a huge resource for gardeners, nurserymen, garden designers, researchers, plant breeders and those interested in historical gardens and landscapes. Having these plants part of a registered conservation scheme makes sure that their beauty, history and useful properties (perhaps as food or medicine) are protected for generations to come.[6]

I had learned a little bit about national collections while working at the Royal Horticultural Society, and I thought it would add an important dimension to the project to see this ‘living library’ of specimens. I am grateful to Tony for allowing me to visit and photograph the collection in 2019.

Figure 19. View of part of the collection, 2019

Figure 20. View of ginkgos growing in 'Air-Pots' - "The majority of the plants are currently being grown in special containers, Air-Pots. This is to ensure that they develop healthy root systems in readiness for planting in the future." https://www.npcginkgo.org/

Figure 21. View from above of a group of smaller specimens

Figure 22. View of part of the collection

Figure 23. Close-up of cultivar 'Survivor'

Figure 24. Close-up of cultivar 'Joe Stupka's Broom'

Figure 25. Ground level view of smaller specimens

Figure 26. Close-up of cultivar 'Troll'. I was ambivalent about the drop of water - it seemed closer to the fetishising aesthetic of Instagram than the practical aesthetic of the national collection. However, the drop of water was real, and in the end, I felt it was appropriate to embrace that ambivalence.

Figure 27. Close-up of grafted stems and labels of cultivar 'Beijing Gold'

Transplantation: A response in fragments to Claire Reddleman’s ‘Ginkgos of the British Isles’ (Jan van Duppen)

A while ago Claire Reddleman invited me to respond to her research project Ginkgos of the British Isles, which invited a distributed collective effort in documenting Ginkgo trees as part of everyday living environments. Reddleman set out a call and invited the public to contribute pictures of Ginkgos through the social media platform Instagram. The project engages with the complex history of this particular species and hopes, in her words, to ‘develop an imaginary of Britain as an island place that is constituted from global sources’. She worked with the generated Instagram feed of Ginkgo pictures and translated this small collective archive into collages—layering and reinserting historical maps that trace the species’ trajectory from China to the British Isles. This return to historical maps could have the danger of performing a nostalgia for a lost Empire, it might have fixed these trees back into historical trajectories of colonialism, exploitation, and racism. Yet, these trappings appear to have been avoided as the crowd-sourced contemporary photographs of Ginkgo trees pierce through these historical maps, they disrupt the reduced representations of territories of empire. The collages escape the framings of the map, a Ginkgo tree leaf full of dew wets the paper, a map of London takes the shape of a Ginkgo leaf, these sorts of translations help to complicate our understanding of the temporal and spatial trajectories of this species. My response to Ginkgos of the British Isles has been simmering at the back of my mind whilst work obligations took over and the pandemic struck, I started to notice Ginkgos on my walks in London and followed the project’s progress on Instagram. Instead of writing up a cohesive linear text, I found it would be most appropriate to respond in fragments to Reddleman’s project. The quotations and images included here crossed my path whilst thinking through its collages. I invite the reader to loiter amongst these fragments as they might help to question the multiple transplantations of the Ginkgo tree.

Figure 28: Young Ginkgo Tree Leaf, 20 June 2021, Bloomsbury - London, Image: Jan van Duppen

Verpflanzen

‘Übersetzen signifies “translation” in the Latin sense of traducere, ‘to lead across’ ‘To translate’ is to bring a discourse across from one language into another, that is to say, to insert it into a different milieu, a different culture. Translation is not to be understood as a simple ‘transfer’ or as a pure linguistic ‘version,’ but instead within the general development of the spirit. This idea, already present in Luther, would be taken up by Goethe, Herder and Novalis, and in a general way by the first romantics that considered this exchange between languages as the condition of Bilduing (Berman, The Experience of the Foreign). Schleiermacher’s theory of the methods of translation, which favours the reader’s encounter with the foreign, is likewise completely based on the analysis of this movement. ‘Translation’ is thus considered as a ‘transplantation’: to translate is to transplant [verpflanzen] to a foreign soil the products of a language in the domains of the sciences and the arts of discourse, in order to enlarge the scope of action of these products of the mind (Über die verschiednen Methoden)’.[7]

A culture not of roots but of routes

‘The predominant academic conception I’d initially inherited envisaged cultures as settled, stable, traditional, and continuous with their origins: what we would call a ‘roots’ conception. Paul Gilrloy, particularly, criticized this as generating a mode of thought which he believed carried with it an inevitable commitment to a cultural or an ethnic absolutism. This critique made it possible to reimagine cultures as what James Clifford and others designated as ‘travelling’ ones: cultures, on the move’, constantly reconfigured through ‘discovery’, conquest, migration, adaptation, enforced assimilation, resistance and translation. In other words, a culture not of ‘roots’ but of ‘routes’, which invites a mode of interpretation which I have been designating here as diasporic’.[8]

Exhale, inhale

‘Street trees are central characters in narratives about urban health. Often the only living element on a street, trees indicate a neighbourhood’s vitality. While an abundant canopy of lush, robust, and long-living trees conjures associations of health, safety, and quality of civic life, a sparse, broken, dying canopy instead reflects disinvestment, social decay, and disease. These associations are both ideological and real. On the one hand, as living organisms, trees in the city have long symbolized an implant of “nature”; they are seen as a natural salve – die or thrive based on investment and maintenance; they register the systemic and spatial inequalities that exist within the city. When they flourish, they improve the air that people breathe in, the very stuff of human survival. As trees exhale, humans inhale’.[9]

Figure 29. Found Ginkgo leaf, 31 January 2021, Angel - London, Image: Jan van Duppen

Illicit pickings

‘Despite the bioculturally diverse conditions supporting foraging in Seattle, institutional regulations, land-use policies, and urban greenspace management practices often specify which plants can go where, who may engage with them, and how’.[10]

‘Species status is a central concept, one drawn from the concerns of conservation science, guiding urban green space management. The concept has given rise to a robust and rather expansive network comprised of humans, technologies, and ideologies dedicated to the removal of ‘alien invasives’ as well as reintroduction and maintenance of particular suites of ‘native species’.[11]

‘In addition to influencing species assemblages, urban managers also influence how people interact with plants and mushrooms in the city. For example, when city horticulturalists plant non-fruiting cultivars, picking fruits and nuts from city trees such as cherry, plum, and ginkgo is clearly not intended and moreover, is rendered impossible. Furthermore, urban managers normalize certain nature practices through Seattle’s municipal code, which prohibits the removal of plants and plant parts from city parks without authorization. Yet, city park officials and volunteer restoration groups go to considerable effort and expense to remove Himalayan blackberry and other forgeable species (e.g., knotweed, holly, garlic mustard), altering the use potential of existing urban spaces and creating an inherent management contradiction to the blanket prohibition against removing plants’.[12]

Gleaning

‘Above all, as a fugitive of Europe’s landscaping practices, Ailanthus requires us to sharpen our peripheral vision: emerging by chance, these trees easily escape structured observation. You never know exactly where to find them. An analytic that tracks ruderal ecologies in the city can therefore cultivate modes of attention that utilize chance and gleaning as a practice of social inquiry rather than focusing on bounded units, predictable political economies, and coherency’.[13]

Figure 30. ‘Ginkgo Health & Beauty’, 23 March 2021, Fitzrovia - London, Image: Jan van Duppen

Embrace

‘The Ginkgo grows at the southwest corner of the Garden, its thick trunk and meandering branches render visible the wise old age of this living fossil. The tree is subject to its own transformations, seasons and cycles and exists in relation to three centuries of Europe’s Social Histories. I walk up to the tree’s large trunk and embrace its resilient form. Around me, cover crops shoot shallow roots into the earth. English ivy winds its way through the foliage and fixates itself onto the ginkgo, meandering upwards. A moist climate and wet weather conditions invite green moss and lichen to take refuge on the ginkgo’s woody exterior. Large, entangled forms of the tree’s thick trunk spiral and branch outward to catch the sun’s rays. Steel wires tie together the most precarious of branches to decrease probability of the tree breaking in a storm. From the steel bands, I trace the outlines of one peculiar branch. From it, hangs a bushel of ginkgo seeds, hundreds of them’.[14]

Resilient

‘However, despite these shortcomings, Sommer’s and his student’s work ultimately facilitated the revitalization of the tree canopy in Dresden. The renewed attention paid to street tree planting in the city also inspired nurseries to cultivate resilient species that could resist many of the shortcomings of urban environments, such as Tilia tomentosa, Sophora japonica, Platanus x hispanica, Ginkgo biloba, Corylus colurna, Sorbus latifolia, and Sorbus intermedia, as well as several species with small tree crowns that could be planted in narrow streets’.[15]

Social uproar

‘The ginkgo tree was brought to Estonia at the end of the 19th century as an exemplar of a taxonomically and evolutionarily rare species. The tree carried also connotations in terms of the cultural space which it embodied and symbolized – this particular specimen originated from Germany and was associated with German culture through associations with J. W. von Goethe and his time, but also through the German roots of gardening in the Baltic provinces. When the tree was drawn into the centre of social uproar in the 1980s, it had been ‘domesticated’ as part of the local milieu and cultural memory of Estonians, while the foreign origin of the species and the specimen was pushed to the margins of cultural memory. This demonstrates that changes in cultural memory can go hand in hand with changes in the delimitation of cultural space and vice versa, and non-human organisms which share their living space with humans may acquire a metonymic significance once they are perceived as an integral part of a certain valued environment’.[16]

Medicinal

‘In many countries such as France, the USA, and China, plantations have been established to cultivate G. bilobafor the supply of ginkgo leaves to the pharmaceutical industry. Application of biotechnology through tissue culture and genetic engineering are choice approaches for conservation of the species and to meet industrial raw material demands for production of ginkgo herbal supplements. The low yield of ginkgolides and bilobalides and the slow growth of the tree along with low yield of the compounds in undifferentiated tissue are impediments to the supply of the compounds, especially the ginkgolide B that shows promise as highly antagonist against platelet-activating factor, which is involved in the development of many respiratory, cardiovascular, renal, and central nervous system disorders’.[17]

Figure 31. Young Ginkgo Tree, 20 June 2021, Bloomsbury - London, Image: Jan van Duppen

Orientalism

‘For their exhibition at the Biennale, Gilbert & George created a completely new group of large 25 pictures using an advanced computer technology that they had spent two years perfecting. Entitled Gingko Pictures, the new works used leaves from Ginkgo biloba trees collected from a park in New York as both a point of departure and recurring motif. This particular species of tree, Ginkgo, was carefully selected as it is no longer rare and the trees can nowadays be found in avenues, parks and even in the streets close Gilbert & George’s home in east London. Ginkgo is revered in the Far East, where it is associated with longevity and reputed to have miraculous powers. These extraordinary properties act as a metaphor for the spirit that runs throughout the 25 pictures. The predominance of the rich golden yellow in many of the pictures is synonymous with the colour the leaves turn in the autumn months. Gilbert & George’s Pavilion installation featured some recurring themes that make their work and visual language so distinctive: symmetry, mirroring, bold colours and large grids’.[18]

Exhibiting #GinkgosOfTheBritishIsles: The booklet

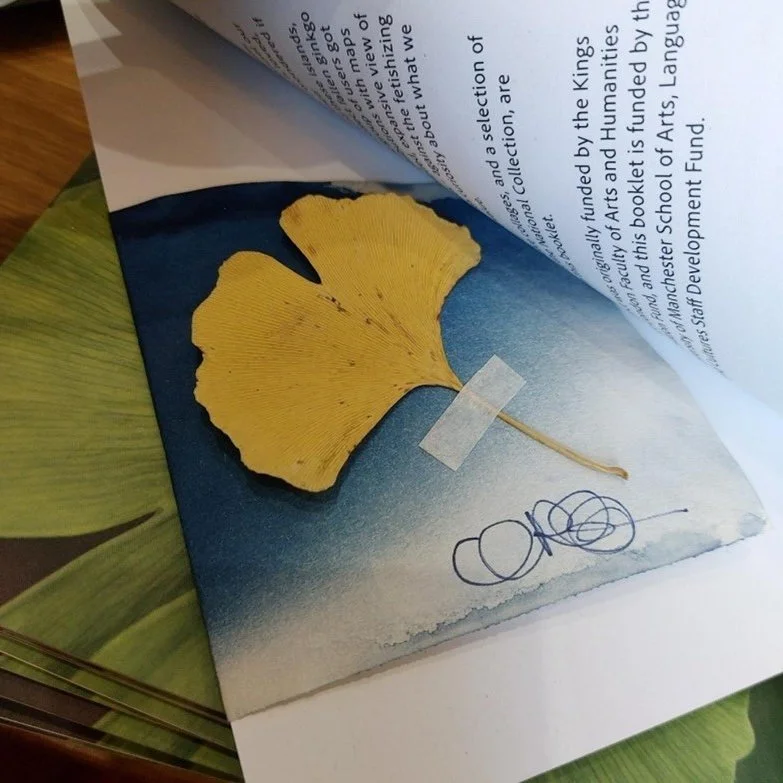

In 2025, I shared the project with participants in the Living Maps Network Conference, whose theme was ‘more-than-human mappings’. Each participant was given a copy of the mobile exhibition, as I was thinking of it – collecting a leaf from the ground, as it were, and tucking it away to keep.

Figure 32. The exhibition booklet with cyanotype print slipcover

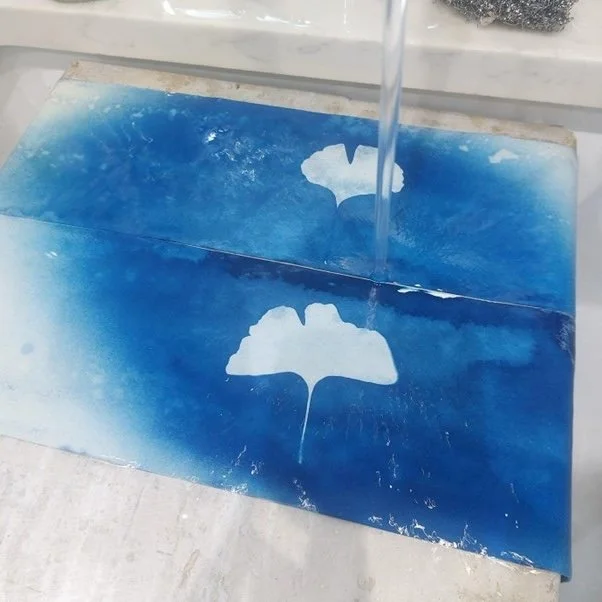

I collected ginkgo biloba leaves from the streets of Amsterdam the previous year, in an imagined connection with the first ginkgo that arrived in Europe and was brought to Leiden’s Hortus Botanicus (the botanical garden). Leiden is less than 50km from Amsterdam, and I wanted to make a material connection between the Netherlands and my project’s focus on the British Isles. I made cyanotype prints from the Amsterdam leaves, fashioning the prints into a kind of slipcover for each book.

Figure 33. Developing the cyanotype prints under running water

Finally, a physical leaf was attached to the inside cover, forming a final, ‘real’ representation of the ‘thing itself’, after all the photographic, cartographic and digital mediations. Each booklet was, like each leaf and each cyanotype, a unique object.

Figure 34. One of the affixed Amsterdam ginkgo leaves

Notes

[1] Berger, J. (2008). Ways of Seeing. Penguin Classics.

[2] Reddleman, C. (2017). Cartographic Abstraction in Contemporary Art: Seeing with Maps (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315200064

[3] Reddleman, C. (2019). Disrupting the Cartographic View from Nowhere: “Hating Empire Properly” in Layla Curtis’s Cartographic Collage The Thames. GeoHumanities, 5(2), 514–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2019.1631203

[4] Atkinson, K. (1998) . Human Croquet. Black Swan.

[5] Postcards from the bagne (https://figshare.com/projects/Postcards_from_the_bagne/91310),

[6] https://www.plantheritage.org.uk/national-plant-collections/what-are-the-national-collections/

[7] Auvray-Assayas, C., Bernier, C., Cassin, B., Paul, A., and Rosier-Catach, I., 2014. To Translate. In: B. Cassin, ed. Dictionary of Untranslatables - A Philosohical Lexicon. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 1139–1155.

[8] Hall, S. and Schwarz, B., 2018. Familiar Stranger. London: Penguin Books.

[9] Hutton, J., 2013. Reciprocal landscapes: Material portraits in New York City and elsewhere.

Journal of Landscape Architecture, 8 (1), 40–47.

[10] McLain, R. J., Hurley, P. T., Emery, M. R., & Poe, M. R. (2014). Gathering “wild” food in the city: rethinking the role of foraging in urban ecosystem planning and management. Local Environment, 19(2), 220–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2013.841659

[11] Green Seattle Partnership 2012:

https://council.seattle.gov/2012/12/04/green-seattle-partnership-funded-by-council/

[12] Poe, M.R., LeCompte, J., McLain, R., and Hurley, P., 2014. Urban foraging and the relational ecologies of belonging. Social & Cultural Geography, 15 (April), 1–19.

[13] Stoetzer, B., 2020. Ailanthus altissima, or the botanical afterlives of European power. In: M. Gandy and S. Jasper, eds. The Botanical City. Berlin: jovis Verlag GmbH, 82–90.

[14] Pekal, A., 2020. Assembling the Natureculture Garden: A Diffractive Ethnography of the Utrecht Oude Hortus. Utrecht University: Master Thesis.

[15] Dümpelmann, S., 2020. Seeing, surveying, and sorting urban trees: the 1970s street tree project in Dresden. In: M. Gandy and S. Jasper, eds. The Botanical City. Berlin: jovis Verlag GmbH, 91–99.

[16] Magnus, R. and Sander, H., 2019. Urban trees as social triggers: The case of the Ginkgo biloba specimen in Tallinn, Estonia. Sign Systems Studies, 47 (1–2), 234–256.

[17] Isah, T., 2015. Rethinking Ginkgo biloba L.: Medicinal uses and conservation. Pharmacognosy Reviews, 9 (18), 140–148.

[18] British Council, 2005. Ginkgo Pictures by Gilbert & George - British Pavilion Venice Biennale [online]. Available from: https://venicebiennale.britishcouncil.org/history/2000s/2005-gilbert-george [Accessed 1 Sep 2021].