From Mapping to ‘Walking With’

How the River Poddle Made me Walk With Her & What I Learnt From it

by Laure de Tymowski (she/her)

Mapping the more-than-human?

In many ways, the more-than-human is the radical other, so how do we go about knowing and mapping it? In this short piece, I give a reflective, grounded, embodied account of my attempt to map the river Poddle as part of my PhD research assessing climate justice in South Dublin.[1] While I had first envisioned my river mapping project as the dispassionate task of drawing a river line on a map background, through intense socio-material and affective interactions, the river Poddle hijacked my initial river mapping project and turned it into a shared epistemological practice. In other words, the river became active co-mapmaker in its own mapping project.

Mapping prep work: reading a lot of theory or flying by the seat of your pants?

There are many approaches to fieldwork, either initiating it with a significant amount of theoretical and conceptual baggage in mind or more as a blank slate (acknowledging that the slate is never fully ‘blank’). In my own mapping project, no preparatory academic reading was conducted before initiating fieldwork. While acknowledging that all approaches have their own potential, I believe that the present account illustrates well the value of the ‘blank slate’ approach. Going into the ‘real world’ with no predefined theoretical or conceptual framework in mind may seem scary and somehow careless, but in my mapping project it allowed me to ask questions and connect with my own embodiment and emotions in ways that may have been different with a more theoretically/conceptually crowded mind.

That being said, at a later stage of the research, three theoretical encounters in particular greatly helped me make some sense of my river mapping experience and I now briefly introduce them before going into the more empirical hows of the initial project unfolding. To begin with, Karen Barad’s agential realism enabled me to fully see rivers as knowledge producers.[2] Defining knowledge production as material-discursive boundary-making practices, they argue that “discursive practices” are not limited to (human) “speech acts” but centrally encompass “the ongoing material (re)configurings of the world” (pp. 821-822). The two other theoretical encounters have more to do with the methodology/method approaches to producing knowledge with rivers. While I conducted my fieldwork without knowing about them, they greatly helped me reflect on it and put into words my own epistemological interactions with the river Poddle.

A most useful approach to co-producing knowledge with the more-than-human was conceived by Bell et al. in the form of what they term “engaged witnessing”.[3] “Engaged witnessing” as a research method framework assumes knowledge production as a fully shared practice whereby all human and more-than-human participants are altogether subject/object of knowledge production. Mutual learning/becoming is achieved through the recognised ability of all participants to be both emitter and receiver, whether sensually and/or affectively and/or materially. Although “engaged witnessing” methods are always tailored to best suit all human/more-than-human knowledge producers involved, be it a lace monitor, a diamond python or Angophora Costata trees, they share some common grounds: a recognition of “the affective nature of encountering non-human actors” and an openness “to being changed, moved or shifted” (pp.137-138).

The third encounter was with Toso et al.’s “walking with” method.[4] While the method resonates with many dimensions if not all of Bell et al.’s “engaged witnessing”, it specifically drew my attention due to its river walk focus. In Montreal, three researchers “walk with” the St. Pierre River, experiencing intense socio-material and affective interactions with the river as the walk unfolds. A dimension explored further in the “walking with” compared with the “engaged witnessing” approach is its reflective engagement with historical inequities and uneven power dynamics: “walking with” demands that “we examine our own assumptions, understandings and perceptions of the city we live in, as well as our own positionality within it” (p8). During the transformative walk, the researchers are led to interrogate various dimensions of their own knowledge production practices and to which extent they might re-enact or challenge settler-colonialism and capitalist assumptions.

My initial river mapping (colonising?) project

The river Poddle rises in the city of Tallaght in South Dublin and flows into the river Liffey at Wellington Quay in Dublin’s inner city. Its estimated length is 11.6 km and its catchment area approximately 16,400 ha.[5] From its source down to the city centre, the river runs half overground and half underground through an alternance of residential, industrial and green areas. Over centuries, it has been heavily engineered to respond to different urbanisation concerns with its underground culverting being a main dimension of such a man-made alteration.

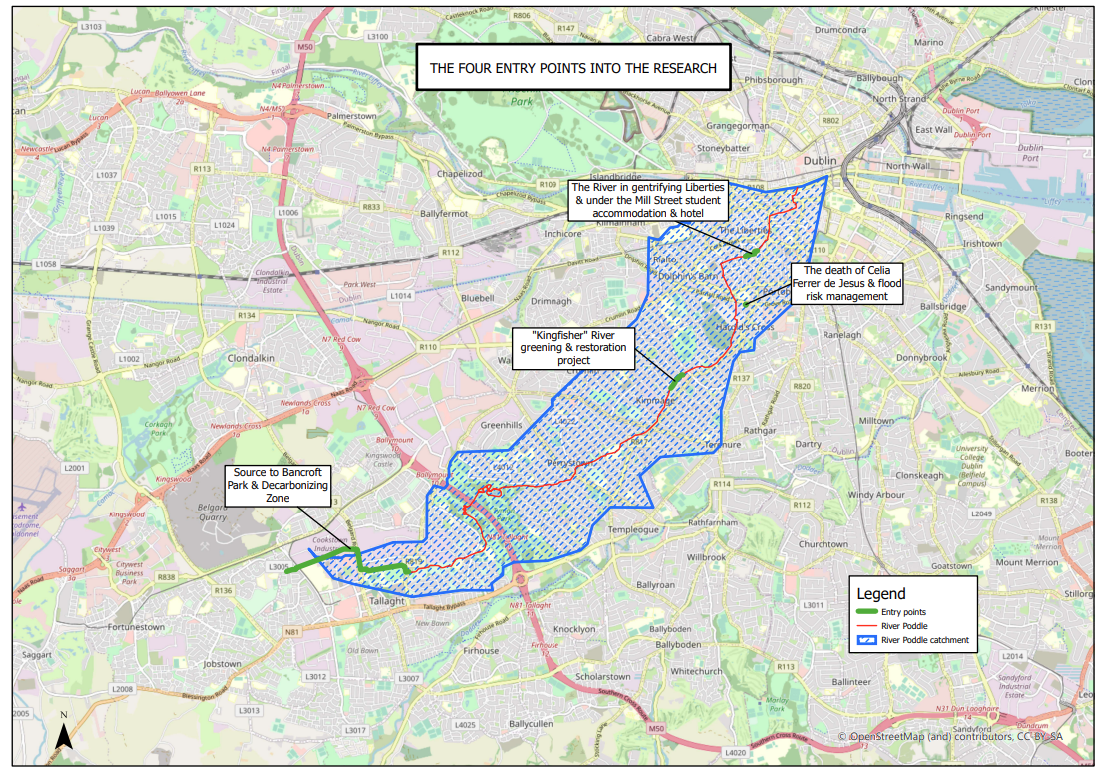

The river Poddle and its catchment have been at the heart of my PhD project assessing climate justice in South Dublin. Centrally, the river catchment boundaries were used to define the spatial focus of the research project. Its four climate adaptation/mitigation case studies are located within those boundaries (Figure 1): a catchment-wide flood alleviation scheme in response to a deadly flood event; a decarbonizing project involving the recycling of an Amazon data centre waste heat to power a local district heating scheme; a river greening and restoration initiative; and, finally, two re-densification developments in the Liberties, a fast-gentrifying neighbourhood of Dublin South. Due to the centrality of the river in the research, I felt I had to find ways to collect some sort of data about it. Starting to look at some of its mappings, I noticed several discrepancies between them regarding both its overground and underground sections. It led me to think that much of my data collection on the river Poddle would be about pinning down its overground/underground location throughout the catchment and produce a ‘final’, ‘decisive’, ‘comprehensive’ mapping of the river. At this stage, my understanding of ‘mapping a river’ was mostly reduced to the act of drawing a river line on an existing map background.

Figure 1: The river Poddle and 4 case studies within its catchment boundaries

Unable to access such a ‘final’, ‘decisive’, ‘comprehensive’ mapping of the river through desk-based research alone, I realized I had no choice but to go on the ground and ‘walk the river’. It seemed to be the only way to dissipate, once and for all, all mapping uncertainties. The river walk was to be documented through a research diary as well as through photographs and videos when relevant along the way.

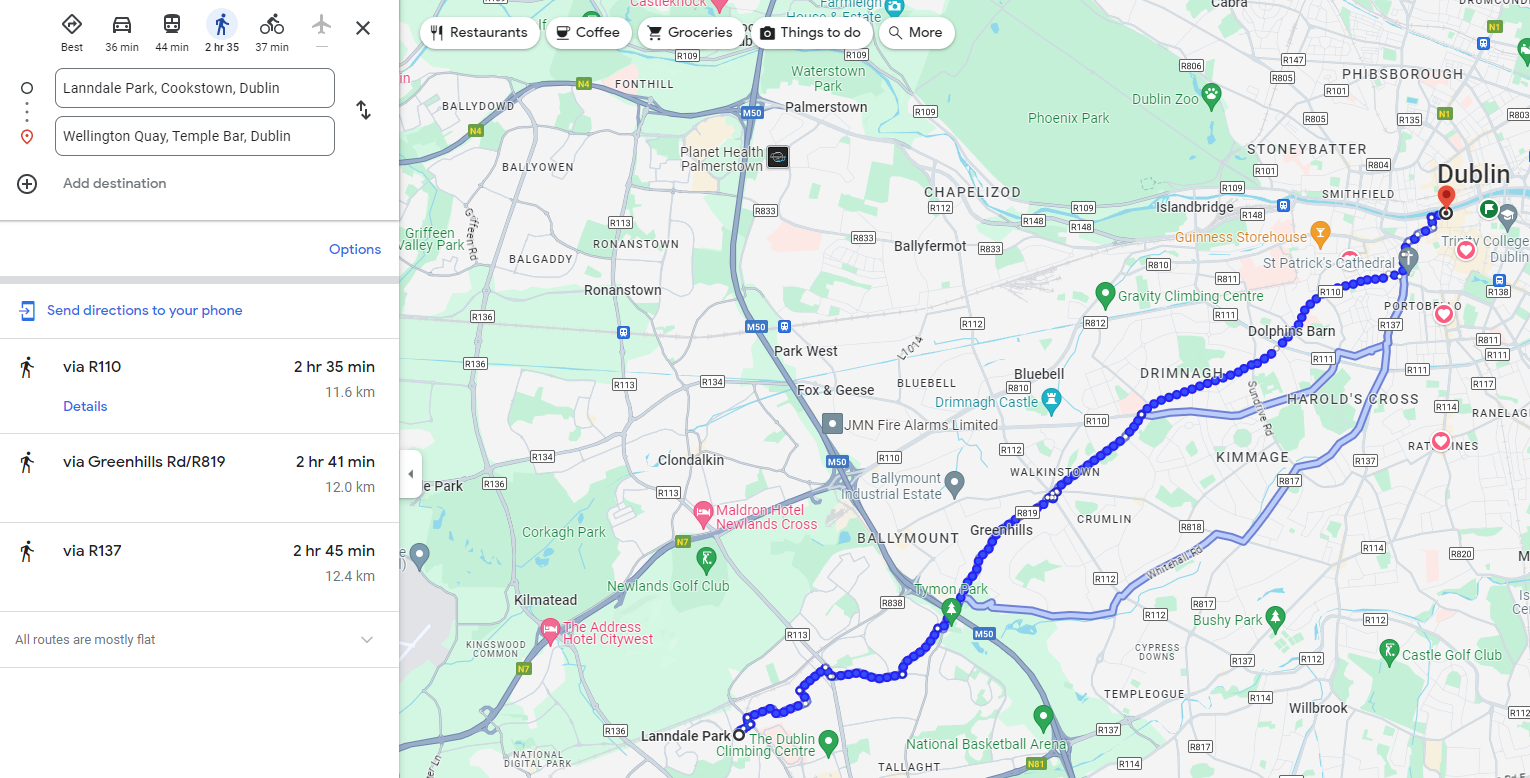

Walking the river seemed straightforward and practically achievable in a short amount of time. The walking distance between its presupposed source location and meeting point with the river Liffey at Wellington Quay was roughly 12 km (Google Maps estimate, Figure 2). My walking pace being around 4 km per hour, I had no doubt that, even if allowing for some resting and photograph/video time, I would complete the walk within a day. I was planning to structure the walk as follows: from upstream to downstream and as parallel as possible to the river so as to be as fast as possible. My initial concern was to cover distance and land surface in a systematic manner, it was all about quantity and efficiency. The professional hiking outfit I was wearing and sporting food and drinks I had in my rucksack on the day of the walk reflect well such a concern (Figure 3). I was going to conquer this river within a day!

Figure 2: The Google Maps estimate

Figure 3: My “professional hiking outfit”!

The river Poddle takes over!

In the early hours of a hot summer morning of July 2021, I left my home in Dublin South to complete the planned river walk. I had decided to start it on the Tallaght Technological University campus where I had heard from local residents that the river could be seen running. The campus was located in the upper part of the catchment, which allowed me to keep up with my initial plan to organise the walk from upstream to downstream. The implementation of my carefully thought river walk project, however, did not quite go according to plan. Rapidly, I was confronted with the difficulty to find the river:

My first inquiry on the campus was laborious and I immediately understood that finding the river Poddle would be far more complicated than I had expected. I had left totally unprepared and disorganized, thinking that I would only have to ask a few people on site to be directed to the river or, better, that there would be obvious signs pointing to the river. I was totally wrong. I asked two university staff if they could direct me to the river Poddle but they obviously had no idea of what I was talking about. A security guard checked his phone and gave me directions to what he thought was the nearest waterway to the campus and I was first really excited about it before realizing that he was actually talking about the Whitestown Stream, a nearby Dodder tributary. (…) Thinking of it now, I still remember how tired I was, how difficult it was to walk these long distances without really knowing where to go. I had never expected that looking for an ‘urban’ river would be so difficult, almost impossible, at least it felt that way on the day because of the exhaustion and heat. I was so surprised, I thought everyone would know about the river, the river that had founded Dublin City. I just could not have anticipated that it was so deeply buried. Despite being ‘open’ on this part of the campus, it was totally forgotten and unseen. This is where I understood that visibility was not just material but that it was socially, culturally produced. (Research diary extract, July 2021)

The contrasted visibility of the half-overground, half-underground river, both “materially” and “socially” produced, resulted in a strange paradox. On one hand, some underground sections of the river at the centre of touristic attractions (such as the section running under the Dublin Castle) or promoted in high profile medias such as The Irish Times were highly visible.[6] On the other hand, some overground sections of the river as the one on the Tallaght Technological University campus received much less attention and therefore remained mostly invisible.

The particular socio-material arrangements of the river became determinant in how the river walk unfolded in its first hours and thereafter. While struggling to locate the river, I was also rapidly confronted with my own embodied limitations. The exhaustion and difficulty to deal with the heat made me realise that it would not be physically possible to complete the river walk in a day as originally planned. In contrast with the Google Maps walker, I was not just covering distance in a vacuum. My embodied progression was tied to the physical and social environment I was immersed in: the high temperature and contrasted river visibility.

The hot summer day and contrasted river Poddle visibility, however, were not all. What greatly influenced the unfolding of my river walk, above all, was the deeply affectionate, almost obsessive relationship that grew between the river Poddle and I in the first hours of the walk. Not finding the river rapidly became a subject of concern, like when you are not able to locate someone you care for. Illustrative of the depth of my attachment to the river were the efforts I deployed over time to establish its location as well as the intense emotional response it prompted whenever they proved successful:

Pursuing my explorative walk on the campus, I follow the river as far as I can before realizing that the river can still probably be seen a little further up before plunging underground and I deduce that I should be able to catch a glimpse of it from the warehouse on the other bank. The site is gated and I go to the reception area to ask permission to enter the site for a brief moment. The site manager agrees to my request but insist on accompanying me as visitors have to be supervised at all times. He walks me to the river and there I see it, a large open section of it. The moments I discover a new open section of the Poddle are always magical. I feel incredibly happy and I just want to jump for joy but I also feel it might not be appropriate in front of the site manager and I just smile widely while chatting with him and trying to keep excitement in my voice to an acceptable level (Research diary extract, summer 2021).

From the ‘river walk’ to ‘walking with’

The described socio-material and affective interactions with the river, in turn, radically transformed the time-space of my mapping/walking project. At the end of the first day of the walk, instead of the imagined triumphal arrival at Wellington Quay, where the river Poddle joins the river Liffey, I had barely managed to walk something like a third of the length of the river. As a result, I made the decision to give myself a second day to complete the walk, which transformed into a third, a fourth, a fifth… From there, after a few days into the walk, things started to change. In terms of the walking rhythm, I started to slow everything down. From a relatively fast-paced walk with only short technical breaks to rest, drink and eat, I went on to walking slowly, taking breaks whenever I felt like it, observing whatever had drawn my attention for how long I felt like it, opening myself to being distracted by the river and all its surrounding inhabitants/activities at any moment of the walks.

After the rush of the first days to get somewhere before a certain time and to evaluate the progress of my river walk mostly in terms of distance covered (the Google Maps approach), my walking trajectory itself took a very different shape: instead of the initially planned straight line as parallel as possible to the river line, it started to be a lot more about going round in circles, going back and forth countless times, going round in circles again, standing still instead of walking, moving slowly, listening to the river instead of wanting to walk it at any cost. In many ways, the river had made me adapt my walk to its contrasted visibilities: “standing still” and “going round in circles”, I was finally ‘walking with’ the river Poddle.

In the end, what I kept calling “river walk” throughout my research project underwent a radical ontological transformation. “Walk” was no longer understood as the act of covering a distance between two points by posing on the ground one foot after the other. “River walk” became a multiplicity of things: sitting by the river for a short while, checking some detail of a built infrastructure on the riverbank, visiting the river because it was making me happy or for no reason at all or out of concern after heavy rain or a pollution incident (Figure 4). Likewise, the temporality of the walk completely changed: from the initial quantitative, efficiency-oriented time-space of the walk, based on the Google Maps estimate it was to be completed within a day, my ‘walking with’ the river Poddle has continued until this day so for over four years since 2021.[7]

Figure 4: “Visiting the river after a pollution incident” (oil spill)

Other ways of mapping

What did I see through the newly imposed time-space of my ‘walking with’ which I would have missed otherwise? After my failure to complete the river walk in a day, from mapping/walking as ‘conquering’, I went on to see mapping/walking as ‘renouncing’, as an act of humility: neither “comprehensive” nor “to speak for everyone”, “to everyone”, “about everything”[8]. Time spent walking with the river, which extended as days passed, was not about “mastery and control”[9] anymore. While I had first naively looked for the river Poddle, after weeks and months of ‘walking with’ I started to perceive the river as a multiplicity of rivers. My river Poddle was one among many in a web of unevenly visible rivers.

The river Poddle “playground”

Slowing down my walking pace enabled me to start ‘seeing’ the river through the eyes of many past and present local children: as a “playground” (recorded interview, local resident). The first realisation of the existence of the river Poddle playground was when the slowing down of the walk allowed me to pay attention to a couple of ropes hanging from trees at one location of the riverbanks. The hanging ropes were in fact improvised swings used by local children to go from one bank of the river to the other. The swing spot (Figure 5) is highly popular among local children and teenagers and adults are also welcome to make use of the swing, at least I was. The space is managed informally but nonetheless productively as swings have been built, rebuilt and rearranged countless times over the last couple of years. Many times at a later stage of the research, the river Poddle was described, documented and ‘mapped’ as a playground during recorded interviews:

My first memories of the Poddle would be growing up and playing in the Poddle or playing in the Park across from the Poddle.

We used to go on our bikes and we’d be jumping the river on our bikes

There is a few houses on my block and we used to, we were on one side of the river and the other kids were on the other side of the river so, one of our kind of games were like, building bridges from debris (...) we would spend the summer kind of like defending our bridge and trying to reck the other kids’ bridge

Figure 5: The “swing spot”

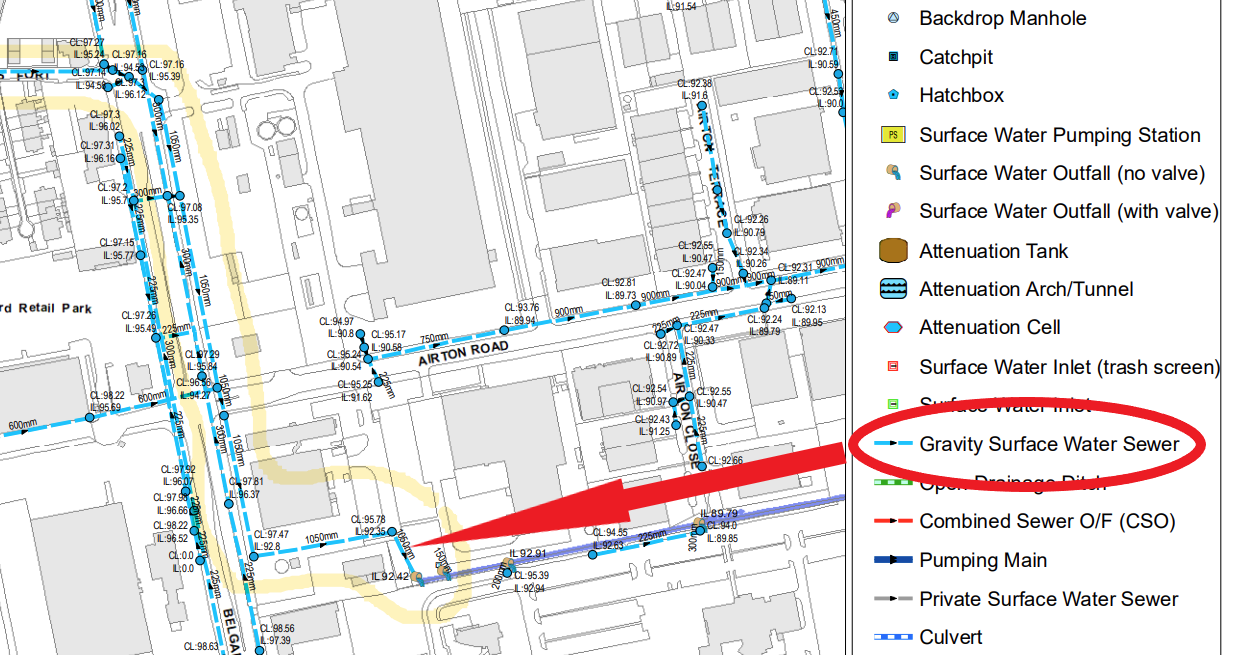

The river Poddle “gravity surface water sewer”

Another significant river Poddle I was able to ‘see’ through the ‘walking with’ was the Poddle of the state and commercial actors. It seems that the main objective of these public and private actors was to make the river disappear. It was to prevent it from becoming an obstacle to more profit-oriented development of the immediate catchment of the river. The erasure of the river was most significant in its upper catchment where it flowed through former industrial land targeted for large residential and commercial redevelopments. In this part of the catchment, the river was mapped by state (Figure 6) and commercial actors (Figure 7) as anything other than a river, including as a “gravity surface water sewer”. Un-mapping practices are facilitated and in turn reinforced by the material arrangements of the river which is mostly culverted underground at this location. In this context of strong social and material erasure, the “going back”, “going round in circles” and “taking time” of the ‘walking with’ became pivotal. As illustrated by the following extracts from my research diary, it is only through the time-space of my ‘walking with’ that I was able to locate the made-to-disappear river Poddle (bold added):

Going back upstream (Research diary entry title, summer 2021)

It is when I go back to planning applications, this time taking the time to search them thoroughly, that I finally start finding traces of the river upstream of its campus sighting (Research diary extract, summer 2021)

I spend a lot of time walking the ground of the Hospice trying to catch a glimpse of the river. (…) I spend a lot of time searching near the walls, in the botanic garden, everywhere between walls and hedgerows, am starting to feel a little obsessed about it and not so rationale anymore. (Research diary extract, summer 2021)

Going back upstream (15/10/2021) (Research diary entry title, 15/10/2021)

Anxiety and paranoia are so high that I decide to go back upstream to check the river (Research diary extract, 15/10/2021)

Figure 6: Local authority mapping of the river Poddle underground culvert as a “gravity surface water sewer”

Figure 7: Signposting of the river Poddle underground culvert as a surface water pipe on a private housing redevelopment site

Main learning

So how do we go about mapping the more-than-human? While the present account describes some of the practical steps taken towards shared river mapping practices in the context of a PhD research project, its main learning is about the centrality of sustaining critical, reflective spaces throughout mapping processes. As argued by Toso et al., “walking with” demands that we critically engage with our own assumptions, understandings, perceptions and positionality. Only through such critical spaces may the epistemic agency of the more-than-human in mapping projects be captured, acknowledged and fostered.

Thanks

Huge thanks to all who have contributed in one way or another to the doctoral research at the origin of the present piece, with special thanks to the river Poddle for walking with me with such patience and generosity! Huge thanks also to the Livingmaps Network editorial team for welcoming our walk in their journal and for all their behind-the-scenes labour.

Notes

[1] Laure de Tymowski, https://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/id/eprint/19039/1/Laure-de-Tymowski-thesis.pdf.

[2] Karen Barad, https://doi.org/10.1086/345321.

[3] Sarah Bell, Lesley Instone, Kathleen Mee, https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12346.

[4] Tricia Toso, Kassandra Spooner-Lockyer, Kregg Hetherington, https://doi.org/10.16997/ahip.6.

[5] Nicholas O’Dwyer Ltd, River Poddle Flood Alleviation Scheme Planning Report.

[6] Patrick Freyne, https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/underground-dublin-a-pilgrimage-through-an ancient-tunnel-network-1.4662108.

[7] See research blog https://river-poddles.ie.

[8] Marion Young, Justice and the Politics of Difference, Princeton University Press.

[9] Joan Tronto, https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700103004200.