More-than-human psychogeography

on “bat-like” places and imaginary geographies

Jin-Kyu Jung & Ted Hiebert

Abstract

This paper highlights one of the critical moments in an interdisciplinary collaboration between an urban geographer/planner and a visual artist, in which we use a brainwave sensor and visualization as a way to map out affective, cognitive, and imaginative geography. Throughout our collaboration, we have explored different ways of seeing, knowing, mapping, and imagining, bringing together sympathetic trends in creative and qualitative forms of GIS and geovisualization and contemporary art. The project we discuss in this paper—What is it like?—is conceptualized as a creative re-interpretation of psychogeography, thinking about psychogeography less in terms of the psychological dimensions of real space and more as a contemplation of the mind’s spatiality. The proposition is that mental space can be thought of as, well, space—and can thus be considered through a geographic lens, or at least through a geographic metaphor. This project explores the geography of a world that is imagined differently (e.g., imagining ourselves to be someone or something else) and how we might map the experience of imagining without ignoring its context or quality (subjective, empathic, imaginary, or otherwise).

Keywords: imagination, psychogeography, imaginary data, geography and arts, creative geovisualization

The Project: What is it like?

What is it like? is an experiment in psychogeography, taking literally the idea that thoughts and ideas might be seen as places we can go to and attempting to start discussions about what this reconceptualization of the mind might mean. The project is also an engagement with what we call imaginary data—by which we mean a form of data that refers not to empirical phenomena but to the processes of imagination themselves. In this sense, imaginary data operates on several levels: metaphorically (as a figure for subjective, affective experience), critically (as a challenge to the empiricist expectation that data must be objectively verifiable), and methodologically (as a participatory way of scaffolding and visualizing the act of imagining itself). We are not so much trying to map the imagination as to structure and support imaginative engagement—treating imagination as a space one can enter, explore, and perhaps even measure, without reducing its qualitative complexity. It is less a survey of the mind and more of an attempt at providing direction or possibilities. It is like a guided meditation but with a twist—not designed as a self-help tool but rather as a conversation about what happens when we treat seriously the places that our minds are able to take us—mapping the mind’s spatiality.

The project is also a response to—and in some ways a critique of—a 1974 essay in the field of consciousness studies by a researcher named Thomas Nagel. The essay was called “What is it like to be a bat?” and, in it, Nagel argued that there is nothing that it is like to be a bat. It was a comment about the subjective nature of consciousness and the problem of subjectivity. He called it “nothing” because what it’s like to be a bat is as incommensurable as the question of what it’s like to be you or me—perhaps even more so as we consider the more-than-human dimensions of such questions. He said that there is “something it is like” to be a conscious being, but that this “something” cannot really be understood scientifically. He went further to suggest that "we are completely unequipped to think about the subjective character of experience without relying on the imagination," something that—for Nagel—was a problem. In contrast, our project centers the unique capacity of the imagination to provide encounters with that which cannot be known directly, as an embodied critique of Nagel's assertions.

The structure of the project is rather simple. Participants are invited to think and talk about bats, aided when possible by presentations from experts in the field. For our project, Dr. Sharlene Santana—a bat researcher from the University of Washington—gave a lecture and answered questions on her research about bats. Participants were then invited to spend a short period of time imagining what it is like to be a bat. We recorded their brainwaves using a commercial-grade electroencephalography (EEG) sensor, which also provided a visualization of the participant’s brainwaves. This data was mapped later and cross-referenced with standard brainwave bandwidths (alpha, beta, delta, and theta) which allowed us some insight into the various states of cognition and immersion experienced by each participant. After their visualization sessions, participants answered a short questionnaire designed to give us some anchor points for their particular experience of the experiment.

An artist sits at a table, imagining what it is like to be a bat

An artist sits down in a darkened room, filled with the sounds of bats and a large projection of a cave. They have just spent an hour discussing bats, listening to experts on bat behaviour and habitat, and thinking to themselves about personal associations and experiences they would relate to the animal. Now, sitting down in a darkened room, they have been tasked with silently imagining what it is like to be a bat—in whatever ways their minds wander and meander and dream. While they imagine, their brainwaves are recorded and visualized while others look on. Soon it will be their turn.

The artist imagines hanging upside down in a cave, given permission to lose themselves to the saturation of an imaginary moment. Dislocated from their usual upright position, blood rushes to their head as they gaze and listen around them. Did you know that a bat’s feet lock when they sleep—like a muscle cramp or a pitbull’s jaw—which is how they avoid falling when hanging upside down. The artist stretches their wings and finds a pleasant breeze in the damp cave, a rustling around them as they become aware of other bodies, smells, and high-pitched squeaks. They become aware of hundreds of others, a crowd, a flock, a murder—actually, a group of bats is called a colony and for good reason—they congregate in large numbers, sometimes in the hundreds, and effectively take over the spaces they inhabit.

Apparently, there are over 1300 species of bats, which also comprise a fifth of all mammals on the planet, according to Dr. Santana. And so the artist continues, eyes dimmed in the dark, hearing and smell becoming dominant senses, reaching out with their imagination to try and hear the echoes in the cave, to feel the sounds bouncing around, such as to gain a sense of orientation. They imagine dropping from the ceiling and flapping wings to emerge into a night sky, sensing others around them with such skill that flight formations and deviations and tornadoes of wings and ears and hungry mouths are formed.

They imagine hunting for fruit or insects, the thrill of a predatory chase, the pivot that emerges when anything else protrudes into the sensory landscape. They fly, perhaps with a sense of excitement and novelty. And then perhaps they remember they are in a room, wired to an EEG sensor, being videotaped and observed by their peers. They might be forgiven if they lost themselves for a moment to the imaginary excursion—indeed, it would be a shame if they didn’t. The return from that imaginary space carries its own disorientation, a reminder that the mind’s geographies are both intimate and spatially expansive—mapped not in the room but through the imaginative journey itself.

A geographer sits at a table imagining the (non)representation of data

A geographer sits at a table and imagines the strange status of the device on their head. It’s a consumer-grade EEG device designed to measure brainwave patterns and record them for later analysis. There are thousands of data points being accumulated and a visualization that gives real-time representative presence to the acts of thought and imagination, all parsed according to the alpha, beta, delta, theta frequencies used to map the happenings of the mind. And yet the happening mind doesn’t see itself this way.

Because the project is about the imagination in any case, a different way to describe what is being represented in the sessions might be as a form of imaginary data—data that functions simultaneously as record, critique, and provocation. At first glance, data and imagining seem to be opposites. Yet here, their tension is productive: the data inevitably fail to represent the actuality of experience, while nonetheless affirming—through this very failure—that something real and affective is taking place. Ceci n’est pas une chauve-souris—this is not a bat. In some way, we might see this as a conceptual sequel to Magritte’s (1929) The Treachery of Images, where the painting of a pipe declares its own failure to be a pipe. Likewise, our visualizations of brain activity are not bats, nor even direct images of thought, but simulacra that expose the gap between experience and its representation. Yet unlike Magritte’s cool detachment, our “economy of simulacra” is grounded in human and more-than-human participation: visualizations that anchor imagination itself as both subject and method.

In some ways, it feels like a journey, a wander, a trip of some kind. It is an act of consciousness if it is anything at all. Perhaps, as simple as an act of holding space. There is nothing bat-like about any of it, and yet here the “nothings” are mapped in a certain sense, brought into space even if no space was actually involved. Imagining a bat is not an abstract activity but a specific one that, in this case, outputs a (non)representation of experience—an image that fails to capture the moment yet succeeds in holding space for its spatio-temporal and affective trace. It becomes, paradoxically, a map of nothing that gestures toward the “something it was like,” circling back to Nagel’s (1974) articulation of the unmappable character of consciousness.

This layering requires a kind of psychogeographic imagination in which certain spaces can be agreed upon even if their particularities remain elusive. The representations map a certain kind of conceptual contour, a space in which something happens, even if the experience of space itself cannot be experientially reproduced. No representation, just a series of markers of experiential intensity, designed to cultivate an awareness of the performative possibilities of the mind. In order to mark an absence as a presence what is needed is to approach the imagination geographically—or rather, psychogeographically—the idea being that imagining a bat might be seen as a space/place within the human mind to which we can go if we want, which is as rich as we make it, and which has no specific expectation of content but rather only one of volition and engagement. The data says nothing about the experience itself—it simply marks a representational intensity. The experience, rather, is generative. The map doesn’t describe the experience; it just signals to us that it’s a possible place to visit—or, better, a possible way of visiting that particular place.

A differently non-human imagination

One might imagine all the possible data in the world—synthesized, perhaps, as only intelligent machines and algorithms might do—forming a complete picture that nevertheless lacks that crucial dimension of “what it is like.” All the measurable somethings are accounted for, yet one still evades capture: the something for which there is nothing it is like.

An artificial intelligence might imagine a bat in such a way as a manifestation of data at a particular point in virtual and algorithmic space. Except that that's not quite true, but not because data can’t be thought of as algorithmically spatial. Rather, because there is some kind of something else also in play in algorithmic systems, something systematically seen as a problem rather than a trait. Despite attempts to build perfectly quantifiable systems, generative AI models reveal a familiar paradox: they too make things up. The technical term for this phenomenon—“hallucination”—marks an intriguing re-emergence of imagination within the machine. Technological culture, so confident in its mastery of simulation, suddenly finds itself unsettled by its own imaginative excess.

One beautiful anecdote—an article by Chris Moran (2023), a lead editor at the Guardian, titled “ChatGPT is making up fake Guardian articles. Here’s how we’re responding.” In the article, Moran describes an email received from a researcher asking for details about a piece that the Guardian had published a few years before. They scoured their archives and even asked the reporter who authored the article, but nobody could find it. The headline seemed plausible—consistent in tone and subject—but no such piece existed. ChatGPT had invented it. “It sounds like it could have been written by me,” the journalist admitted, recognizing the unsettling accuracy of the machine’s imaginative fabrication.

We might think of the predictive algorithms that will soon shape our interactions with urban architectures and environments. Yet none of this is ever simply material. It was the psychogeography of the city that once alarmed the Situationists—and perhaps it is the psychogeography of Nagel’s pronouncement that unsettles us now. What is it like to be an algorithm, charged with completing the thoughts of those who may have forgotten how to imagine?

We call this beautiful precisely because it is so unsettling. AI researchers and journalists alike rush to correct, combat, or reprogram generative systems—to remove their capacity to hallucinate. The gesture feels familiar: a reprise of Nagel’s own impulse to strip human thought of its imaginary excess. Yet when an AI is prompted to write, it is being asked to make something up—to imagine. No surprise, then, that it does. What is perhaps more of a surprise is that it’s also quite good at it—imagining what it is like, what could be, as if a certain someone who writes about certain things might have also said a certain something. It’s perhaps not bad as a starting point for intelligence, artificial or not. It’s definitely more than human.

Discussion

The project is designed to sit at an interdisciplinary intersection of art and geovisualization. As an art project, it is a thought experiment—treating the imagination itself as a creative medium for experiencing the world differently. The experience is unique—each participant has their own version of bats, their own story of the experience, their own point of reference for how immersed they decided to go. Seen as an art project, it is not the data that matters—it is exactly the fact that the data is inaccessible to anyone except the participants themselves. One has to imagine what it might have been like for them to imagine, and in so doing, engage with the idea that there are different ways to imagine.

As a geovisualization project, the goals are perhaps similar, with one important exception that the end goal is not just to imagine but to constitute the imagination as a holistic, creative, and qualitative form of data and experience. How might we map the experience of imagining without ignoring or reducing its content and quality? The visualization acts here to mark what we cannot see happening. It tells us that there is some kind of intensive activity in play–some kind of imagining, maybe. Yet it tells us almost nothing about what that imagining is like.

“Imaginary data” is data that requires us to imagine in order to engage with it. The EEG readings show peaks, intensities, and levels of cognitive engagement—but these values possess no communicable content without our capacity to imagine alongside them. What is it like? therefore asks its question twice: once of the participant and again of the observer. The imagination is not a problem to be solved but the connective tissue of the project—the psychogeography of a human imagining what it is like to be a bat, or indeed a human imagining what it is like to a human imagining (what it is like to be a bat). At stake is not only the possibility of the more-than-human, but also the recognition that imagination itself—human, algorithmic, or otherwise—is the generative excess through which new forms of representation and understanding emerge. At stake is the status of the imaginary in the larger context of intelligently generated futures.

urprisingly, the Design Museum hosted its exhibition titled More than Human (London 2025) just after the Livingmaps Network’s conference in April 2025, which centred around the same theme. I was excited to attend the exhibition on its opening day, and it certainly met my expectations.

The More than Human exhibition at the Design Museum invites visitors to rethink design outside of an anthropocentric perspective. Curated by Justin McGuirk and Future Observatory, it showcases over 140 pieces that include speculative installations, architectural prototypes, Indigenous cosmologies, and efforts in ecological restoration. As an artist with a focus on mapping, I interpret this exhibition as a form of cartography that examines the connections between humans and non-humans. Like any map, what is included or excluded becomes crucial for analysis.

The curatorial strategy organises the exhibition into three thematic categories: Being Landscape, Making with the World, and Shifting Perspectives. It seems clear to me that the Design Museum emphasises a progressive journey: from recognising ecological interconnectedness to practicing co-production and fostering perceptual transformation. Visitors traverse through a conceptual framework that evolves from representation to processes of empathy.

Forest Mind: Ursula Biemann (Multi-channel video installation, 2021, duration: 31 minutes 44 seconds). Photo by Jina Lee

Many individual pieces aim to redefine relationships across various species and scales:

Alusta Pavilion (Elina Koivisto & Maiju Suomi) embodies cohabitation cartography by incorporating insect cavities into architectural surfaces, illustrating potential coexistence between humans and insects while blurring traditional habitat boundaries.

Living Seawalls (Reef Design Lab) serves as an ecological base map with modular structures designed to restore marine biodiversity along urban coastlines. Here, design goes beyond metaphorical implications to enact tangible cartographic interventions that establish new habitats.

Pollinator Pathmaker: Perceptual Field (Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg) proposes a radical shift in cartography by visualising landscapes through the sensory experiences of bees and other pollinators. This approach reminds us that while such empathetic representations strive for depth, they remain human interpretations that can oversimplify non-human perspectives.

Pollinator Pathmaker: Perceptual Field: Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg (Wool, cotton, acrylic, polyester cotton, cashmere, 2025). Photo by Jina Lee

Cited from the exhibition caption:

We are used to thinking of gardens as spaces we design for our own pleasure. Alexandra Daisy

Ginsberg's long-running project Pollinator Pathmaker uses an algorithm to design living artworks' that cater to the needs of pollinators instead, providing them with food and shelter. The design of this tapestry has been determined by Pollinator Pathmaker's plan for a virtual garden that could be planted on the Design Museum site.

The tapestry's scale shrinks human viewers to the size of pollinating insects encountering flowers across the seasons, starting with spring on the left. As insects sense the world differently from us, the colours of the tapestry reflect a pollinator's vision, rather than a human's.

Courtesy of Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg

Kelp Council (Julia Lohmann) immerses viewers in suspended seaweed forms that induce sensory disorientation; instead of functioning as a conventional map, it provides an experience rich in texture and scent—indicating that understanding non-human entities also entails being influenced by them.

Kelp Council: Julia Lohmann (Soundscape by Ville Aslak Raasakka, Julia Lohman, Mixed media, 2025). Photo by Jina Lee

Cited from the exhibition caption:

Julia Lohmann invites you to step into a council of seaweed - a gathering of species she collected in Europe and East Asia. Set within a soundscape of the rising and falling tide, this installation offers a new perspective on coastal ecosystems.

The enigmatic forms reveal seaweed's properties and potential as a design material, inviting connection on a human scale.

If we consider that all living things have their own needs and agency, we might ask: what does seaweed think of us? How can we use this regenerative resource responsibly, meeting our own needs while learning to care for seaweed in return?

Courtesy of Julia Lohmann and Ville Aslak Raasakka

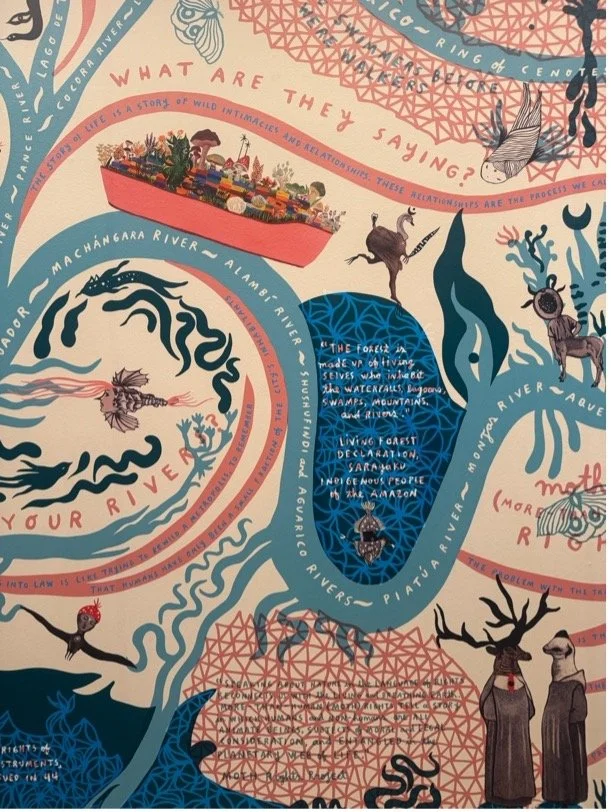

More-Than-Human Rights Mural (Elena Landinez, César Rodriguez-Garavito), represents rivers not merely as physical waterways but as entities that possess legal rights and life. The artwork unfolds like a watershed, intertwining visuals of humans, flora, and fauna with excerpts from legal texts concerning environmental personhood—some of which can only be perceived through red glasses. Consequently, the mural engages in mapping as a form of political expression, prompting inquiries into whose ecological narratives and legal assertions are highlighted and who is responsible for this visibility. Personally, as a citizen of New Zealand, I found it pleasing to see the word Aotearoa.

The More-Than-Human Rights Mural: Elena Landinez, César Rodriguez-Garavito (PVC-free wallpaper, acetate, 2025. Photos by Jina Lee

The inclusion of Indigenous artists like Solange Pessoa and Hélio Melo further enriches the mapping landscape by presenting environments not merely as external spaces but as dynamic entities filled with narratives and shared existence. These contributions challenge conventional modernist cartographies which have typically marginalised subaltern narratives regarding relationality.

What remains uncharted within this context? Initially, underlying political ecologies associated with design practices—such as land dispossession, colonial extraction, and environmental racism—are largely implicit within the display. By focusing primarily on objects and installations alone, there is a risk of overlooking the socio-political contexts shaping these design opportunities. That this exhibition takes place within Design Museum is telling. It marks the circulation of more-than-human thought into mainstream cultural institutions and well-known museums certainly have the power to enhance discussions and influence public perceptions. However, it is essential to be cautious, as they can sometimes serve as containers: environments where radical ecological ideas are admired yet don’t lead into practice. Visitors may briefly engage with non-human viewpoints, but the exit is often a return to unchanged infrastructures.

This contrasts sharply with environments where more-than-human relationships are actively recognised in legal and political contexts, such as the acknowledgment of the Whanganui River as a legal entity in Aotearoa New Zealand. In this case, rivers hold not just symbolic significance but possess legal rights and representation. The gap between gallery exhibitions and legal initiatives highlights the uneven landscapes through which these concepts travel. While exhibitions like More than Human can illuminate such visions, it is within other contexts, like activist networks, legal systems, and critical discussions at academic conferences, that they acquire real transformative power.

Nonetheless, one of the exhibition's core strengths lies in its capacity to effectively transform perceptual frameworks. Works like Pollinator Pathmaker or Kelp Council invite audiences into alternative sensory experiences that challenge typical human-centred perspectives. These interventions can be viewed as counter-mapping efforts reshaping how we perceive our environment. Another significant strength is its fusion of art with design and science; merging speculative ideas with tangible prototypes alongside Indigenous methodologies creates a comprehensive multi-dimensional representation of what 'more-than-human design' could encompass.

Furthermore, within broader discussions surrounding ecological design approaches, More than Human offers terminologies for various mapping techniques, including perception mapping along with material flow interactions among species over different timeframes. From a critical mapping perspective, this exhibition illustrates both the possibilities inherent in cartography as well as its limitations: acknowledging maps’ intrinsic selectivity while remaining politically situated within specific contexts. The showcased works provide imaginative mappings yet may unintentionally obscure historical injustices or structural inequities connected to multispecies interactions.

For those of us working with mapping as critical practice, the goal extends beyond simply interpreting existing institutional maps; it involves the act of reimagining them. This entails exploring the tensions that exist between aesthetics and politics, as well as between imagination and tangible action. As both an artist and researcher, I find this challenge particularly daunting. While the exhibition presents an important opportunity, its true value is found in how these imaginative concepts extend beyond the confines of the museum; infiltrating infrastructures, movements, and practices where non-human entities are not only acknowledged but also empowered to take action.

Its significance extends beyond offering insights into future relationships transcending humanity; it also challenges prevailing cognitive frameworks about our understanding of those connections—underscoring how vital it is for mapping practices themselves to evolve beyond solely human-centric paradigms.

More than Human was shown at The Design Museum, 11th July - 5th October 2025