Exhibition Review

More than Human at the Design Museum

Jina Lee

Surprisingly, the Design Museum hosted its exhibition titled More than Human (London 2025) just after the Livingmaps Network’s conference in April 2025, which centred around the same theme. I was excited to attend the exhibition on its opening day, and it certainly met my expectations.

The More than Human exhibition at the Design Museum invites visitors to rethink design outside of an anthropocentric perspective. Curated by Justin McGuirk and Future Observatory, it showcases over 140 pieces that include speculative installations, architectural prototypes, Indigenous cosmologies, and efforts in ecological restoration. As an artist with a focus on mapping, I interpret this exhibition as a form of cartography that examines the connections between humans and non-humans. Like any map, what is included or excluded becomes crucial for analysis.

The curatorial strategy organises the exhibition into three thematic categories: Being Landscape, Making with the World, and Shifting Perspectives. It seems clear to me that the Design Museum emphasises a progressive journey: from recognising ecological interconnectedness to practicing co-production and fostering perceptual transformation. Visitors traverse through a conceptual framework that evolves from representation to processes of empathy.

Forest Mind: Ursula Biemann (Multi-channel video installation, 2021, duration: 31 minutes 44 seconds). Photo by Jina Lee

Many individual pieces aim to redefine relationships across various species and scales:

Alusta Pavilion (Elina Koivisto & Maiju Suomi) embodies cohabitation cartography by incorporating insect cavities into architectural surfaces, illustrating potential coexistence between humans and insects while blurring traditional habitat boundaries.

Living Seawalls (Reef Design Lab) serves as an ecological base map with modular structures designed to restore marine biodiversity along urban coastlines. Here, design goes beyond metaphorical implications to enact tangible cartographic interventions that establish new habitats.

Pollinator Pathmaker: Perceptual Field (Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg) proposes a radical shift in cartography by visualising landscapes through the sensory experiences of bees and other pollinators. This approach reminds us that while such empathetic representations strive for depth, they remain human interpretations that can oversimplify non-human perspectives.

Pollinator Pathmaker: Perceptual Field: Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg (Wool, cotton, acrylic, polyester cotton, cashmere, 2025). Photo by Jina Lee

Cited from the exhibition caption:

We are used to thinking of gardens as spaces we design for our own pleasure. Alexandra Daisy

Ginsberg's long-running project Pollinator Pathmaker uses an algorithm to design living artworks' that cater to the needs of pollinators instead, providing them with food and shelter. The design of this tapestry has been determined by Pollinator Pathmaker's plan for a virtual garden that could be planted on the Design Museum site.

The tapestry's scale shrinks human viewers to the size of pollinating insects encountering flowers across the seasons, starting with spring on the left. As insects sense the world differently from us, the colours of the tapestry reflect a pollinator's vision, rather than a human's.

Courtesy of Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg

Kelp Council (Julia Lohmann) immerses viewers in suspended seaweed forms that induce sensory disorientation; instead of functioning as a conventional map, it provides an experience rich in texture and scent—indicating that understanding non-human entities also entails being influenced by them.

Kelp Council: Julia Lohmann (Soundscape by Ville Aslak Raasakka, Julia Lohman, Mixed media, 2025). Photo by Jina Lee

Cited from the exhibition caption:

Julia Lohmann invites you to step into a council of seaweed - a gathering of species she collected in Europe and East Asia. Set within a soundscape of the rising and falling tide, this installation offers a new perspective on coastal ecosystems.

The enigmatic forms reveal seaweed's properties and potential as a design material, inviting connection on a human scale.

If we consider that all living things have their own needs and agency, we might ask: what does seaweed think of us? How can we use this regenerative resource responsibly, meeting our own needs while learning to care for seaweed in return?

Courtesy of Julia Lohmann and Ville Aslak Raasakka

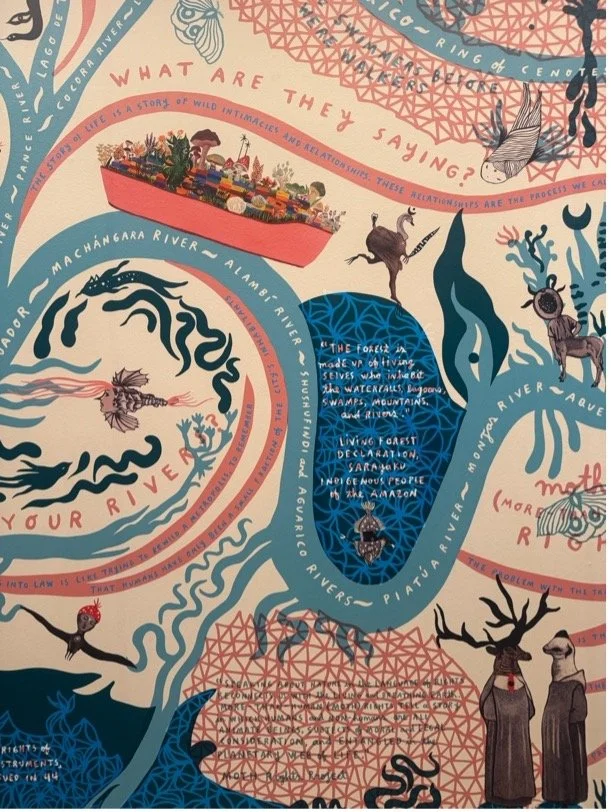

More-Than-Human Rights Mural (Elena Landinez, César Rodriguez-Garavito), represents rivers not merely as physical waterways but as entities that possess legal rights and life. The artwork unfolds like a watershed, intertwining visuals of humans, flora, and fauna with excerpts from legal texts concerning environmental personhood—some of which can only be perceived through red glasses. Consequently, the mural engages in mapping as a form of political expression, prompting inquiries into whose ecological narratives and legal assertions are highlighted and who is responsible for this visibility. Personally, as a citizen of New Zealand, I found it pleasing to see the word Aotearoa.

The More-Than-Human Rights Mural: Elena Landinez, César Rodriguez-Garavito (PVC-free wallpaper, acetate, 2025. Photos by Jina Lee

The inclusion of Indigenous artists like Solange Pessoa and Hélio Melo further enriches the mapping landscape by presenting environments not merely as external spaces but as dynamic entities filled with narratives and shared existence. These contributions challenge conventional modernist cartographies which have typically marginalised subaltern narratives regarding relationality.

What remains uncharted within this context? Initially, underlying political ecologies associated with design practices—such as land dispossession, colonial extraction, and environmental racism—are largely implicit within the display. By focusing primarily on objects and installations alone, there is a risk of overlooking the socio-political contexts shaping these design opportunities. That this exhibition takes place within Design Museum is telling. It marks the circulation of more-than-human thought into mainstream cultural institutions and well-known museums certainly have the power to enhance discussions and influence public perceptions. However, it is essential to be cautious, as they can sometimes serve as containers: environments where radical ecological ideas are admired yet don’t lead into practice. Visitors may briefly engage with non-human viewpoints, but the exit is often a return to unchanged infrastructures.

This contrasts sharply with environments where more-than-human relationships are actively recognised in legal and political contexts, such as the acknowledgment of the Whanganui River as a legal entity in Aotearoa New Zealand. In this case, rivers hold not just symbolic significance but possess legal rights and representation. The gap between gallery exhibitions and legal initiatives highlights the uneven landscapes through which these concepts travel. While exhibitions like More than Human can illuminate such visions, it is within other contexts, like activist networks, legal systems, and critical discussions at academic conferences, that they acquire real transformative power.

Nonetheless, one of the exhibition's core strengths lies in its capacity to effectively transform perceptual frameworks. Works like Pollinator Pathmaker or Kelp Council invite audiences into alternative sensory experiences that challenge typical human-centred perspectives. These interventions can be viewed as counter-mapping efforts reshaping how we perceive our environment. Another significant strength is its fusion of art with design and science; merging speculative ideas with tangible prototypes alongside Indigenous methodologies creates a comprehensive multi-dimensional representation of what 'more-than-human design' could encompass.

Furthermore, within broader discussions surrounding ecological design approaches, More than Human offers terminologies for various mapping techniques, including perception mapping along with material flow interactions among species over different timeframes. From a critical mapping perspective, this exhibition illustrates both the possibilities inherent in cartography as well as its limitations: acknowledging maps’ intrinsic selectivity while remaining politically situated within specific contexts. The showcased works provide imaginative mappings yet may unintentionally obscure historical injustices or structural inequities connected to multispecies interactions.

For those of us working with mapping as critical practice, the goal extends beyond simply interpreting existing institutional maps; it involves the act of reimagining them. This entails exploring the tensions that exist between aesthetics and politics, as well as between imagination and tangible action. As both an artist and researcher, I find this challenge particularly daunting. While the exhibition presents an important opportunity, its true value is found in how these imaginative concepts extend beyond the confines of the museum; infiltrating infrastructures, movements, and practices where non-human entities are not only acknowledged but also empowered to take action.

Its significance extends beyond offering insights into future relationships transcending humanity; it also challenges prevailing cognitive frameworks about our understanding of those connections—underscoring how vital it is for mapping practices themselves to evolve beyond solely human-centric paradigms.

More than Human was shown at The Design Museum, 11th July - 5th October 2025