Mapping Connections

Mike Duggan

I sat down with Debbie Kent, Jina Lee and Kimbal Bumstead, all long time contributors to Livingmaps, to discuss why they became involved in the project, how they developed their interests in maps and counter-mapping, and how mapping continues to inform their arts practice.

Mike

What drew you to mapping, and what kind of mapping do you do? What was it about the Livingmaps Network that caught your attention?

Kimbal

I think it's a very interesting question about whether I was drawn to mapping as a practice or whether it’s something I’ve realised about my work in retrospect, but now I would say that my work is definitely inspired by maps, and by my fascination with maps as tools for discovery.

Thinking about Google Maps and also paper maps, physical maps, I’m interested in this idea that maps are a way to explore, as if going on a journey, by looking at them, you can imagine that you are exploring, or travelling. This idea of looking at a place that you know, or that you don't know, zooming in on places that you know or that you remember, or places which you are fascinated by. I've always had that thing with maps. When I was a kid, I loved going on bike rides and taking the Ordinance Survey maps with me, planning a route and then getting lost, losing and finding the route. What's that? What’s that over there? What could that be? That kind of thing…

I also think about maps as a kind of drawing, so I think about my paintings and my drawings as being a bit like maps. Or a bit like landscapes, or visual things in a landscape. I like this idea that landscapes are maps of themselves, that capture all the traces of what has taken place on, and in them. So it could be the cracks on the pavement or lines in the sand, or the smudgy residue of a melted ice cream, or the tyre marks on a wall in a bike storage room. I think it's that idea of a map being a physical thing interests me, and the idea that a map is a kind of a trace of something that has happened. I've always been fascinated by the notion of the renaissance traveller sailing around the world and drawing the map as they go, tracing it, drawing the outline of the coast, physically marking where they had been. This idea resonates very strongly with my artwork, which involves performative processes, and using drawing or mark making to capture traces of something that happens; an interaction, or an encounter.

I got involved with Livingmaps after I applied for the Contemporary British Painting Prize and by coincidence John Wallet (a Livingmaps co-founder) was doing some work for them and he saw my application. He got in touch to say that I might be interested in this project that he was working on, which was a Livingmaps event about cartography and cinema, so I went along and realized that there's this whole community of people that are engaged with this stuff. I feel like becoming part of this network has cemented the idea that maps and mapping are a really important part of my practice. It made me start thinking about mapping both as a methodology and as a way of explaining some of the process-based stuff that I'm interested in. Maybe I didn't realize quite as concretely before, how important maps are to me, but I do now.

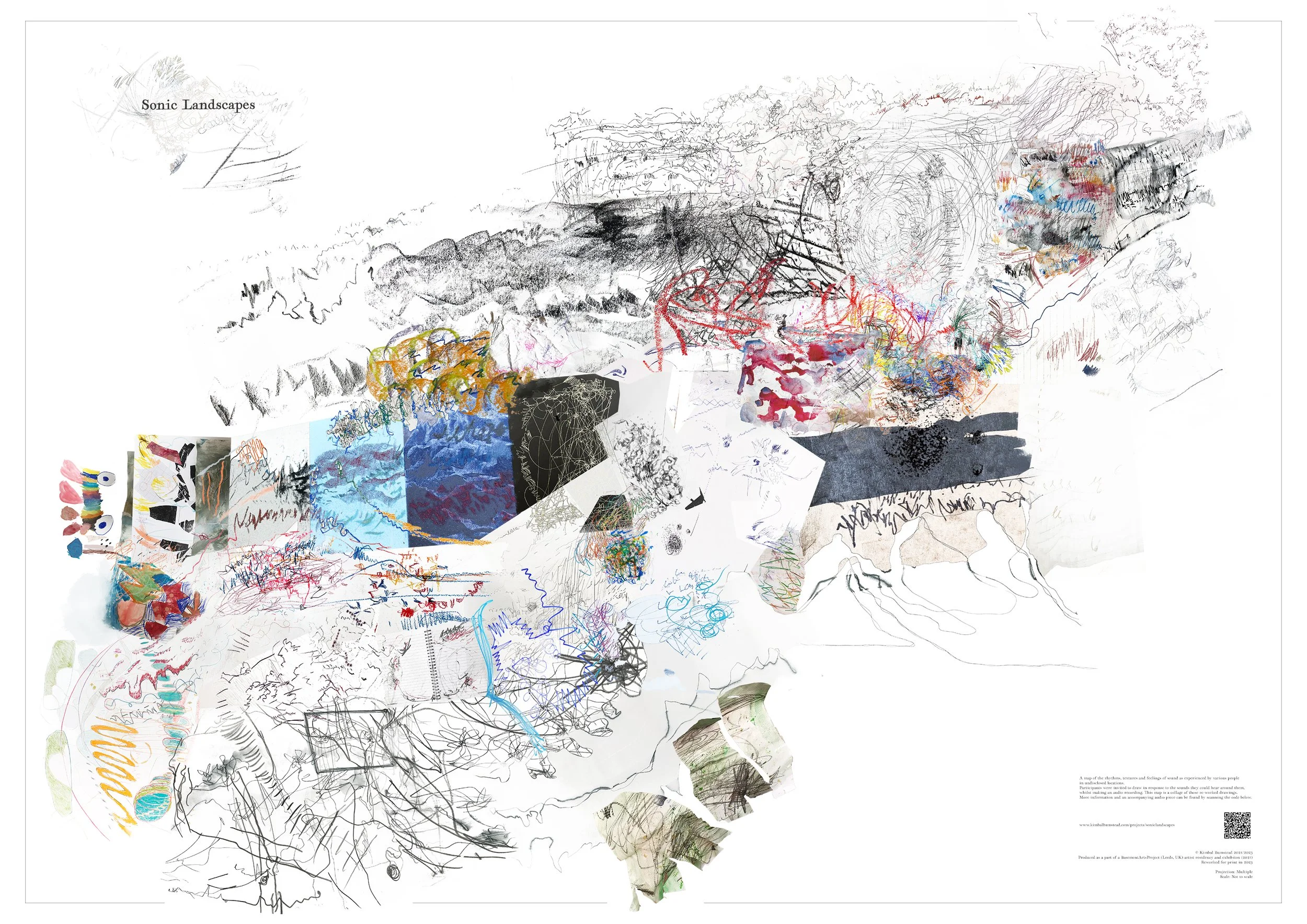

Sonic Landscapes. A map of the rhythms and textures of sonic environments as experienced and drawn by participants in undisclosed locations. Digital Collage, Printed Map and Audio Collage (2021/2023)

The accompanying audio collage is available at https://www.kimbalbumstead.com/projects/soniclandscapes

Jina

My interest in mapping came from an autobiographical aspect. I was born in Seoul, South Korea, but I lived in various countries including the United States, New Zealand, Australia, and currently reside in London, UK. So when people ask me where do you live? I just couldn't situate myself on a conventional map. Later on, when I went to art university I found myself thinking maybe I could make my own map instead of fitting myself into a conventional map. And that's when my mapping started.

In my 20s I was very lucky to travel to many places with my friends. We used to collect at least 10 or 15 maps from the library, or the bookshop, then gather all the places that we wanted to visit. We would design a whole new map before we went on a big journey for a week or two. That idea of layering and creating my own maps, which I still do today, started with these life experiences of living in and visiting different places.

My first funding after I graduated school was received to create an artist project on the experiences of immigrants in South Korea. It was a six-month project. The event took place at a location called Ahansan. According to government data, South Korea remains an attractive destination for low-skilled and low-wage workers who stay on temporary work visas. I established a strong connection with foreign labourers by visiting them every Saturday and opening a temporary laundry shop where I washed their working uniforms for free. The laundry has become a platform where people can freely come and go, share their stories of discrimination in the factory, and more. Since then, I have become more involved with immigrant labour communities beyond my personal experience.

During my PhD research, I discovered similar occurrences in London. A search for immigrant labourers in London led to the development of my TalkingMap method. Although some may argue that it is not a traditional map, however I believe, the process itself can be considered a form of mapping. To me, the maps include participatory and community workshops, audio-led guides, walking tours, poetry, life and memory stories, and more. All of them can be understood as mapping in some way, even if mapping does not always result in the creation of a map.

During the initial stages of establishing the Livingmaps network, Phil Cohen and John Wallet sought my assistance as an intern. I began as an intern with the company. Later, I worked as an editor for a brief period when the Livingmaps Review journal was launched. Currently, I work as one of the directors alongside Mike.

Debbie

I've always had a horrible sense of direction, so I've always used maps to help me find my way. I've always loved walking too, exploring cities in particular and when I was young, before GPS and Google Maps, I thought that memorising the A-Z would give me some sense of mastery of how to get to places, which I didn't have in my body like other people do.

I also developed an interest in maps when working on a piece with my collaborator, Alisa Oleva, that was inspired by the (Jorge Luis) Borges short story called ‘On Exactitude in Science’, which is where the phrase the map is not the territory comes from. A lot of cartographers or people who are interested in maps and countermapping will be very familiar with that story, which is also told in various different forms by different authors. Actually, I think Borges was inspired by Lewis Carroll, who told the version of it in Sylvie and Bruno about making a map that captures every detail. Anyway this made us think about this relationship between representation of place and reality. There was an artist collective called the Boyle Family, who were quite well-known in the 70s, they made these casts of real squares of the world. I was completely fascinated by them and this idea that you could take a slice of the world into the gallery. What did it mean to represent it?

This led us to thinking about how we could deconstruct a map, but still using it to show people's relationship with the city. We called our work the Demolition Project. We would stick a giant map of London on the wall, give people scalpels and ask them if they wanted to destroy something in the city. The price of destroying it on the map with the scalpel, literally cutting it out, was to tell us why they wanted it gone.

We ended up with all these stories about people's relationships to things they wanted to destroy. Originally we thought of it as a very simple thing, but this complexity emerged from it. Right from the beginning we saw how demolition was positive as well as negative. Some wanted to destroy a flyover so they could build housing for the homeless there. Some wanted to destroy the Olympic Park so they could rebuild allotments that had been destroyed for the Games. The map became kind of a vehicle for people's emotions and people's deepest feelings, and also a way to voice their thoughts about town planning or about building design. It was about giving the power back to people to reimagine the city and what it could be like.

We starting doing it in London for a few hours at a festival or even all day at a shopping centre. Eventually we took the Demolition Project to different cities like Manchester and Leeds, using maps of those cities and then we took it to Moscow and did it in an art gallery there. We even ended up giving it to other artists to do at festivals or places we couldn’t get to, like the remote north of Russia.

Around the same time, I was going to Livingmaps talks because they were always really interesting. I remember talking to Phil Cohen about the Demolition Project and and he asked me to become involved with the organisation. Now I edit a section of the journal and have run workshops for Livingmaps. Being involved has consolidated my thinking about what I do and how it relates to maps. Lots of my more recent walking work relates to looking for an embodied way of thinking about maps, for example how you make a mental map in your mind through experience of the senses, so it’s been good for that too.

The Demolition Project

Mike

I want to build on what Debbie was saying there, but to think about your work collectively too. I would say what you all create different forms of mapping, but not in a cartographic sense. There are certainly cartographic elements to some of your work. I'm thinking about Debbie cutting out pieces of cartographic maps for the Demolition Project, or the ways that there are kind of top down views in both Kimbal and Jina’s work. But cartography for me is this formalisation or professionalization of mapmaking, it doesn’t account for all types of mapmaking, especially those forms that want to do more than simply show us where stuff is. I wanted to ask what value you saw in your form of mapping? This is connected to the world of ‘map art’ too in the sense that it comes and goes as a trendy form of arts practice.

Kimbal

As an artist, I often feel the need to justify the value of my mapping projects, in a way that I don’t feel the need to do with my paintings and drawings for instance. People often ask this question in talks or at workshops “What is the value of this methodology?", or “What can we do with these kinds of maps?” and I feel like I am constantly trying to justify it, explain what it is, or why it is relevant. But with my paintings and drawings, or sound work, people accept it as what it is.

You go to a gallery, you see a painting, whether it's abstract or figurative, or whatever, and someone could look at it and be like, OK, I understand what that is – I am looking and experiencing. But when you get into more conceptual realms, it's more challenging to try to explain to people what they are looking at and what they should, or could do with it. It's an issue that I often stumble with when trying to describe my practice as it sits between disciplines. It requires more storytelling, or contextualisation.

I see myself first and foremost as an artist, for whom mapping is an integral part of my practice, but I also don’t feel as though I make ‘map art’, or even art with maps, but rather work that is inspired by maps and mapping.

People often like to see clear results, to have clear understandings, but I think my mapping work is more about the process rather than the product. I think it’s more about looking at what mapping is and what it could be - thinking of a map as a tool to discover, and as a way of connecting to memories and experiences. I’d say that the value in my mapping work is precisely that – valuing, or celebrating subjective experience. It’s about this idea that a map is not necessarily something that captures empirical information, or data, but can be about experience, and can be read or discovered in a multitude of ways – just like a work of art can be.

Debbie

I could build on what you were saying about value. For me the whole value of counter cartography or countermapping, which is what I’ve done, is that it fundamentally subverts the power and control that comes from above in most maps – like the Ordinance Survey started as a branch of the military. It's still a branch of the government and making maps of places is still about delineating whose territory belongs to who and who has responsibility for it. Enabling people to make their own maps, enabling people to look at maps differently is valuable because it opens up these possibilities of seeing the way that we visualize the world. The value of the mapping I do (e.g. the Demolition Project) comes from everyone having some kind of power over the space around them or even from seeing the ways in which power is exerted on them, to sort of expose those things.

Countermapping and our approaches to it are valuable because you're putting a pencil or a pen into the hands of somebody and inviting them to make a trace, something of their own, or putting a scalpel into their hand and saying ‘destroy this’, this map that came from the government.

One project I did early on involved inviting people to pair up. One half of the pair would explore a place and draw their own map of it in whatever way they wanted, and then hand it to the next person who would try and follow that map. What was so interesting about that was the discussions that came out of it and how nobody thought about mapmaking in the same way or visualized a representation of a place in the same way. It opened a whole area to talk about. What was the map? What was the place? What was important in a place? It was just a little thing, but it opened cracks in people's understanding of how places are constructed, how they are controlled and how we navigate them.

Jina

As artists and map-makers, it is important to move beyond conventional maps and include diverse perspectives and stories. To achieve this, interdisciplinary approaches are valuable. The interdisciplinary aspect is where the value lies. I prefer to work with multiple dimensions, not just a bird's-eye view from a single perspective. This allows us to see the world from the viewpoints of people who are often overlooked or forgotten in our society. Not everyone wants to be hidden, although some might. When all diverse stories, regardless of power, are included on the map, it becomes genuine and indispensable.

Coming from Asian culture, I have a unique perspective on nature and its relationship to the world. This informs my approach to map work. Especially when you see old Asian artists’ landscapes and maps, they depict nature in various seasons and weather conditions, capturing the beauty and essence of nature in one work. This approach differs from Western landscapes, where the artist sets a point and draws the landscape in an exact linear perspective. Asians often aimed to convey the artist's emotional and spiritual response to the natural world rather than simply replicating its physical appearance. The focus is not solely on power, viewing nature from above, but rather on coexisting with it. My drawing practice reflects this approach as I strive to present diverse perspectives.

I also appreciate the importance of building connections with both the participants we work with and our colleagues. However, the value of the counter map itself can be difficult to comprehend, particularly for viewers who may struggle to connect with the stories it presents. While the map contains valuable data and knowledge, it can be challenging to effectively share this information with those who are reading it. It is important to find ways to make these counter maps more accessible to wider audiences.

Kimbal

I want to pick up on that because it's very interesting what you’re saying about abstract or cryptic maps being both a blessing and a curse. On one side, when something is very abstract or nonspecific it allows that possibility to be able to tell stories which are hidden or secret, to avoid having to say what exactly happened or exactly where something was. It's more about trying to express the idea or that feeling of a memory or a place, you know? So in a sense, the cryptic nature of these kinds of maps can be a very positive way for participants to share something that they wouldn't necessarily want to tell in a really blatant way.

But then as you said, it can also become a curse because you want people to understand what you have created. Sometimes you make an abstract drawing and maybe it was all very interesting in the process and it was very useful for the person or the people who made them together. They understand it. They know for themselves, but how do you then communicate that to other people, and does it need to be communicated to other people, or is it actually purely about the process of making the map? Working on more abstract types of maps really makes you question what a map actually is and what it is for, I think that is part of the value of it, which is precisely to question the notion of what a map is.

Debbie

Yes, I’d agree with that, but we can also think of different participatory elements too. the artist doesn't necessarily need to meet the participants. Sometimes the participant is just the person who's looking. Their interpretation, or their active engagement with the work can be a sort of trigger to ask these questions, what is a map? What’s the point of it, what's the use of it? What's it saying to us? What's it doing for us? What are we doing to it?

Going back to map art, it's not a terribly useful idea. For example, I do a lot of work with sound or have done a lot of work with sound and there was this great question about the turn towards ‘sound art’ and people were saying, well, that's no more useful than talking about ‘paint art’. Sound has become an element that is available to artists and is something that they can use if they want. I think maps are the same thing. It’s not really about what they are but about how you use them. Layla Curtis’s work for example uses maps, but really, it’s about subverting cartography rather than using it as maps. By combining cartographic maps in impossible ways, she produces something very different that invites the audience in to think about what's going on.

Mike

Whilst we’re talking about participation, you’ve started doing the Growing up in Coastal Towns participatory mapping project with UCL. I'd be interested to know how that's going and what's coming out of that.

Jina

Two workshops have been conducted in Great Yarmouth and Barrow with participants of different age groups. The purpose of these workshops was to encourage participants to reflect on their relationship with these towns. In Great Yarmouth, the groups were divided into those under 20 years old and those in their 60s, while in Barrow, only older participants were involved. Our original plan was to visit six coastal towns, but we have now reduced it to five.

Mapping within the 2-hour workshop timeframe is challenging. The limitations of this counter mapping activity include insufficient time for full development. Developing a comprehensive understanding requires more time. However, we have managed to develop a few more methodologies. Initially, we conducted a workshop where we collectively placed stories and items on a large map. However, having an idea going forward from Sam Whewall (UCL), we will request individuals to create their own maps to allow for more thoughtful sharing.

The task has been interesting as it involves learning the history of the town itself. Although they are all in common being coastal towns, each has unique characteristics. Growing up in these towns is a unique experience that is not universal. Creating these maps reveals different stories from those we are familiar with in larger towns or cities. It's something that we never expected to think about, and it's quite fun to compare how the younger and older generation think about these places. It's really different. Even though we used the same map, the outcome was different. This may be due to counter-mapping, which shows us a world according to the people who are making it.

Kimbal

It's also quite interesting, going back to that question about the cartographic aesthetic, to think about the maps we’ve used for the Growing up in Coastal Towns project, which are printouts of maps that people recognise. We did do some drawing activities and asked people to make their own cognitive maps, like personal journey maps, but we’ve abandoned that methodology now in favour of using the physical maps, the printed OS maps.

I feel like people do respond very well to that. People like maps because they can place themselves on it, whereas drawing is not necessarily something that everybody can do, or rather it is something that intimidates people because they think it needs to look a certain way. Whereas a map is like, this is the map, this is how it is. They recognize it so there is this sense of knowing what to do with it, how to show where this is and where that is. There's an objectivity to it, which is actually very powerful in a way of getting people to share personal stories. I think there is huge value in using ‘real’ geographic maps in participatory mapping projects, as it leads to deep, and located insights into how people experience, remember and imagine spaces and places. For me this was an interesting realisation, because I usually work with very abstract types of map.

Debbie

That's something that I certainly relate to. We (Debbie and Alisa Oleva) started off presenting a huge, printed map to people and found that they were absolutely fascinated by it in a way that was completely unexpected and out of that grew all these stories. I think as a technique for generating other things, generating discussion, generating motion, a printed conventional map is a really interesting place to start. The counter mapping ideas come once you start attacking that map, whether you're drawing over it with highlighter pens or cutting things out of it. It’s a very literal way of overturning its immutability.

Talking about obstacles I was thinking about this idea of instrumentalizing art with cartographic art or counter mapping art, to produce some kind of sociological outcome. I struggle with that. I dislike this idea and also find it difficult because sometimes this kind of work doesn't lend itself easily to these outcomes.

Mike

This is something I've also struggled with from a kind of academic point of view. I think it comes back to this question of value. The responses you all gave to my ‘what is the value question?’ were almost identical to the kind you might get from asking ‘what is the value of art?’ There's something about the expectation we have of maps, that they must provide some instrumental value beyond the process of making them. That idea has been subsumed by industry as much as it has done by academia. There's an expectation that if you produce a counter-map, it must have a use value beyond the process. There's now a whole branch of sociology and geography which is all about using maps to put people's voices on the map, give a voice, but also then an expectation that it will somehow influence policy or be used to shape an outcome of sorts. Once a map has been produced it can generate its own value outside of the makers control too, so the value maybe interpretated or acted on differently by other people not involved in making it. Often it's not interpreted very well and used to serve interests that are quite different from those originally planned.

Debbie

Yeah. It’s like ‘we're giving you a voice. Damn it. Say the right things!’ Often in these workshops people say things you're not expecting, and sometimes that's not even something easy to hear. It's not what you expect or accept, but for me it's really important to invite people and listen to them rather than try and impose what you think they should be saying. I'm very much about the process rather than interested in the outcome.

Kimbal

Yes, exactly. The type of mapping that we do is very much about valuing the process over the outcome.

Debbie

Yeah, and that's difficult.

Jina

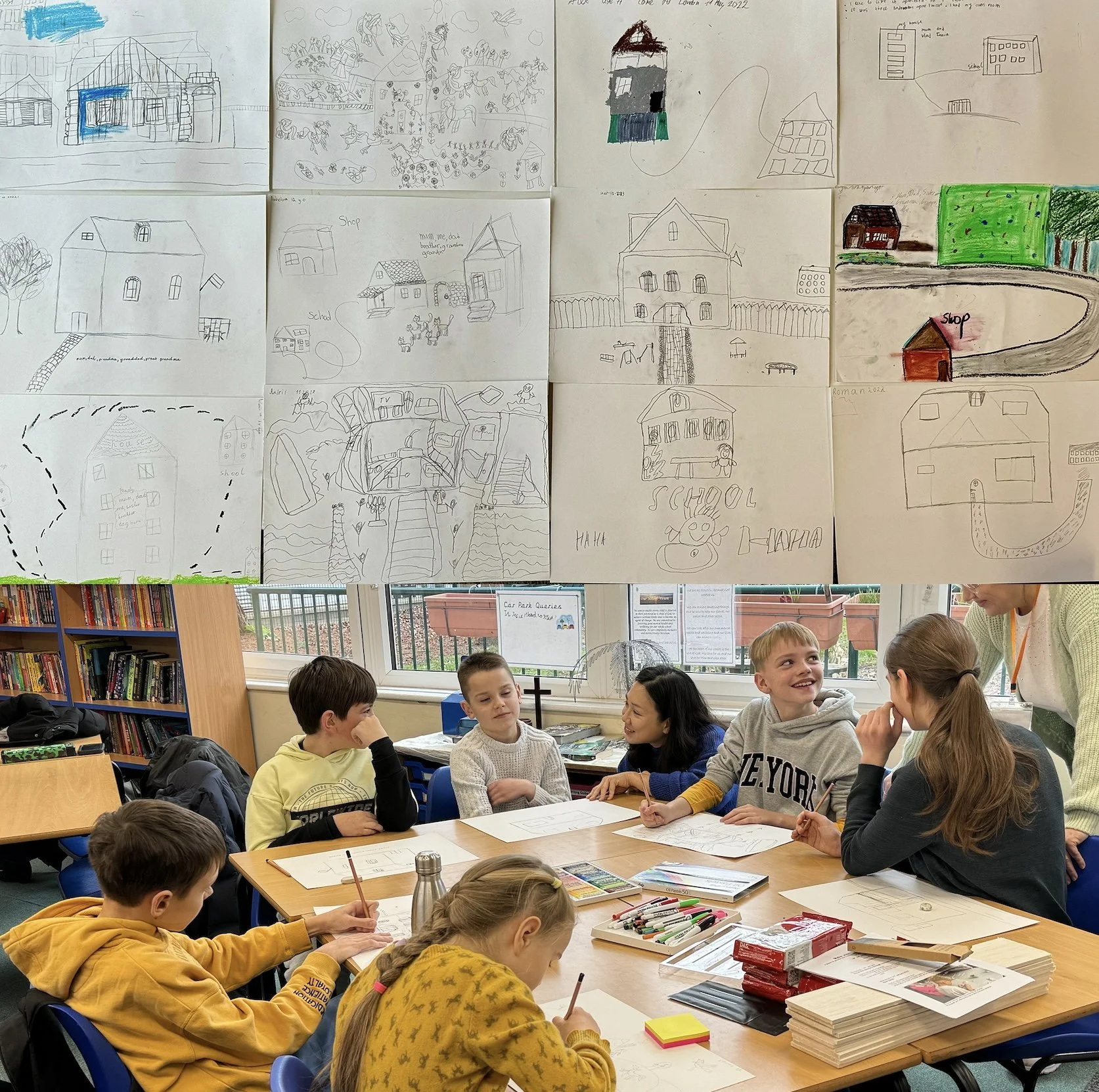

Following Debbie’s thought on the process, the process has become even more important to me recently because I have been working with children more often by chance. I worked with Rosetta Arts and Ukrainian children at Wilberforce Primary School and St Richard's CE Primary School. The children I worked with were around 10 years old. When working with younger people, the process becomes even more crucial as unexpected stories and ideas often emerge during activities such as mapping, drawing, or modelling. Therefore, my focus has been on how to capture these processes accurately. I dislike this term, but I am attempting to streamline the documentation of workshop or project proceedings.

Additionally, we must consider their fragility when undertaking this work. Emotions, particularly those of the Ukrainian children who arrived after the invasion two years ago, are delicate. Although they may appear content on the surface, when we delve deeper into their stories during the workshop, forgotten or suppressed memories and narratives may surface. For me, creating hand-drawn maps on paper has become a helpful way to open up. Although they may not look as neat as cartographic maps, they involve emotions, movements, and directions from new home to old home, making the process more personal. Hope to share the project with you soon.

Make Yourself Home: the Ukrainian Refugee Journey Map, 2024

pencil, colouring pencil, oil pastel on paper

Workshop led by Jina Lee,

Participants: St Mary’s Ukrainian School, Richmond

Mike

I think this is a good place to finish because it leaves questions about the different forms and processes of counter-mapping, and also cements the idea that there is no universal one-size fits all approach to this, which I often see as the goal for those trying to develop some notion of the perfectly contained counter-mapping methodology. Your work and comments show us that this really isn’t possible.

Thanks so much for chatting with me today.